Steven Spielberg Lincoln Part 3

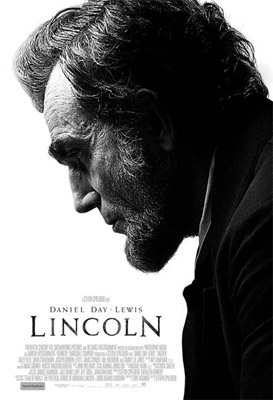

Lincoln

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field, David Strathairn, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, James Spader, Hal Holbrook, Tommy Lee JonesDirector: Steven Spielberg

Genre: Biography, Drama, History

Rated: M

Running Time: 153 minutes

Synopsis: Steven Spielberg directs two-time Academy Award® winner Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln, a revealing drama that focuses on the 16th President's tumultuous final months in office. In a nation divided by war and the strong winds of change, Lincoln pursues a course of action designed to end the war, unite the country and abolish slavery. With the moral courage and fierce determination to succeed, his choices during this critical moment will change the fate of generations to come.

Release Date: February 7th, 2013

Website: Trailer

The House of Represenatives

The outcome of the vote for the 13th Amendment in the House of Representatives was up in the air until the final hour-and it would spark a flurry of some of the most intense debate, political pressure and changed minds ever seen in the chambers of American government. Inside the 1865 Congress, "Lincoln" paints a vivid portrait of American politics in all its grandeur and eccentricity, its love of the art of persuasion and its insistent belief that people of different views can work together.

A key voice in the roiling House debate is that of Thaddeus Stevens, a representative from Pennsylvania, and a so-called "Radical Republican" who pushed not only for the emancipation of the slaves, but for the complete abolition of the slavery system on which the Southern economy was built. Known for his fiery wit and sarcasm, he was another larger-than-life figure in Lincoln's midst-so it was fitting that the filmmakers cast Tommy Lee Jones, known for an unforgettable array of characters, including his Oscar®-winning turn as Deputy Samuel Gerard in "The Fugitive."

"Tommy Lee Jones playing Thaddeus Stevens was perfect," says Kathleen Kennedy. "We just couldn't get over it. I kept asking Tony Kushner again and again, 'Did Thaddeus Stevens really say that?' I think Tommy Lee Jones immediately understood who Stevens was. He appreciated his intelligence and that he was a genuine human being fighting for what was right. He also understood that when it came to the 13th Amendment, he would face a personal struggle and would need to compromise in order to find the means to an end."

Says Daniel Day-Lewis of Tommy Lee Jones: "I don't expect to have a day's work that excites me as much as the day we worked together did. And that really has to do with what he came with and what he was ready for more than anything."

Sally Field had a particularly fun scene with Tommy Lee Jones as Mary Lincoln clashes with Stevens, who as the head of the House Ways and Means Committee infamously tried to have her jailed for over-spending on White House renovations. "I think Mary just despised Thaddeus," she explains. "To her, he was the devil incarnate, not only because he tried to have her jailed, but because he was a radical who often worked against her husband even though he was in the same party. And yet, in the case of the 13th Amendment, he helped turn things around. And what a great character he is!"

Stevens' best-kept secret of all may have been his housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, a widow who worked for him for 25 years, amassing contacts that later helped launch her career as a rare black businesswoman in the 1800s. Demonstrably close, and likely partners in an Underground Railroad that transported slaves to freedom, many historians believe Stevens and Smith were also clandestine lovers. Playing Smith is Golden Globe® and Emmy Award® winner S. Epatha Merkerson.

It was Tony Kushner's script that brought her into the mix. "I love Tony Kushner's humanity, his dialogue, his heart and humour," she says. "When he called and asked if I would play Lydia, I started looking into this character who became this extraordinary businesswoman at a time when a woman of colour would not be allowed to do those things-and I became fascinated."

S. Epatha Merkerson especially relished having the chance to read the 13th Amendment aloud on screen. "The one thing Steven Spielberg kept saying is that, as Lydia is reading, it's the awe of the moment-and that was a perfect direction. Here is a black woman who has lived in a time when her people were beaten, raped and murdered, and their children were snatched from families. She had seen all of that as part of the Underground Railroad and this moment had to be a most incredible release."

Another major voice in the House at that time was the inflammatory New York Congressman Fernando Wood, who was sympathetic to the Confederacy. Fernando Wood is brought to life by Lee Pace, next to be seen in Peter Jackson's screen adaptation of "The Hobbit." Lee Pace says he took his inspiration for one of Lincoln's noted nemeses not only from history but also very much from our times. "My idea going into playing the character was that he's very much like our politicians today. He just wants to keep the fight going and spinning, 'cause as long as his name is in the paper, he's relevant."

Among those whose vote changes at the last minute is Ohio Congressman Clay Hawkins, portrayed by Walton Goggins, best known for his roles on "The Shield" and "Justified." Clay Hawkins was a Democrat who didn't support slavery but felt it might be politically dangerous to vote for the 13th Amendment. Says Walton Goggins of his dilemma: "For some, it was about morality-but my character was also faced with the threat of death if he went along with this vote. He had to take into consideration everything that was going on in the country, maybe the possibility of a peace offering by the Confederates and on top of that his personal safety, and finally doing what, in his heart, felt right."

Lincoln's World

"Lincoln" would take Steven Spielberg not only into one of the most riveting moments in American history, but into fresh visual territory-working in a style at once vivid and raw, strong but minimalist. He took this leap with the same family of acclaimed film artists with whom he has collaborated for decades, including director of photography Janusz Kaminski, editor Michael Kahn, production designer Rick Carter, costume designer Joanna Johnston and composer John Williams. Though each of these men and women have their own creative shorthand with Steven Spielberg, they also knew this was going to be a distinctly different experience.

"This was a very intimate and quiet production, because Steven Spielberg made it all about words and performance," observes Kathleen Kennedy. "This was a more personal experience."

Janusz Kaminski, who garnered Oscars® for "Saving Private Ryan" and "Schindler's List," was intrigued by finding potent but honest imagery for a story that is often about the sheer power of what a man says. "It's a story that really demands the audience listen," he notes. "So when I read the script I immediately started coming up with ideas about how to capture all these words in visuals. It was clear to both Steven Spielberg and to me that there should be a feeling of restraint in the photography-that we should just photograph these unfolding events in the most beautiful, elegant of ways and let the language and performances be at the centre of everything."

He goes on: "We were interested in letting audiences discover the Lincoln they don't know. The film shows a Lincoln who is uncertain, who is vulnerable. And I think Steven Spielberg's staging along with the camerawork, in its spareness, reflect that human side of the president."

Janusz Kaminski wanted a stripped-back sensibility, but also a texture and a palette that would transport audiences-not into something that feels historical but into scenes that could be happening right now. Observes Kathleen Kennedy: "Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski discussed at length the use of colour and light in 'Lincoln.' Steven Spielberg didn't want to make a black-and- white or sepia-toned film; rather, they used a rich saturation of colour that has some qualities of black and white. We also have over 145 speaking roles in this film, so it was important to frame each scene so the characters are taking you to the next beat in the story and not necessarily the camera. That was a bit different for Steven Spielberg."

Though he and Steven Spielberg pored through a plethora of historical paintings and photographs for reference, once on set, they keyed into a more instinctual approach. It became about finding the stark power in quieter moments-Lincoln and Grant talking on the porch while ghostly soldiers ride towards unknown fates; Lincoln standing in the hazy light of the window as he realises the 13th Amendment has just ended slavery in America. "Steven Spielberg is never afraid of strong imagery," Janusz Kaminski comments. "He is very willing to use transcendent moments like these in his storytelling."

Some of Janusz Kaminski's favourite scenes came inside the chaotic House of Representatives. "Those scenes are all about the performances and the debate of ideas. There are some interesting dolly moves characteristic of Steven Spielberg's visual sensibility, but it is all very understated," he explains.

Some of Janusz Kaminski's favourite scenes came inside the chaotic House of Representatives. "Those scenes are all about the performances and the debate of ideas. There are some interesting dolly moves characteristic of Steven Spielberg's visual sensibility, but it is all very understated," he explains. These scenes also electrified Kathleen Kennedy. "The camera never moves in these scenes unless it's in the service of the narrative. Steven Spielberg wanted to show the human intricacies of how a democratic government works, so it was never about cutting from one talking head to the next but about really giving the audience a sense of how the arguments were progressing," she says. "More than anything, Steven Spielberg wanted to capture the volatility of what was going on in this political battle."

Throughout the film, Janusz Kaminski aimed for period naturalism in the lighting. "It's 1860, so Lincoln's world would be lit with gas and oil lamps," he notes. "We used a lot of existing light sources, light coming through windows, light from lamps, but we also created light sources to better serve the storytelling. Smoke was also utilised to give the film a moody patina and because Lincoln's environs would have been filled with it. There were constantly people smoking pipes, smoking cigars and there was no ventilation, so rooms all had that smoky atmosphere."

For Janusz Kaminski, "Lincoln" not only revealed another side of the U.S. president but another side of the director with whom he's collaborated for so long. "This was not just another movie," he says. "None of the movies I've made with Steven Spielberg are just another movie, but there is something so significant about 'Lincoln.' It is a piece of entertainment but it is also a story of great importance."

Janusz Kaminski's camerawork would become one of a piece with the production design of Rick Carter, who, in a poignant symbol of a nation coming full circle, used the former Confederate city of Richmond, Virginia, to recreate 1865 Washington D.C. in the film.

Rick Carter was deeply moved by the script's portrait of Lincoln and saw right away that he would need to walk a fine line in his design work. "The opportunity and the challenge for me was that while it's a big story, it's also a very intimate one," he comments. "It's very much inside Lincoln's world, his office, his living quarters, the streets he walked through. The richness of that world had to be finely detailed and the set decorators and I went to extraordinary lengths to help make every single moment as real as possible-and at the same time, a bit expressionistic."

As with the photography, an elegant simplicity was central to his concept. "The film is carefully designed so that what you see in Washington D.C., or the battle sites, never distracts from what the film really focuses on: Lincoln and the friends, family and rivals around him," Rick Carter says.

Early on, Rick Carter began to search for a location that would serve the film's diverse needs. He roamed through Tennessee and Virginia, taking a history-rich tour of preserved Civil War sites to get the feeling of those places deep into his bones. Of all the potential locations, it was Richmond, Virginia, that transported him most, and he felt its well-preserved buildings could support a 19th century reality like nowhere else.

"History is alive in Richmond in a way you don't find it in the rest of the country," he explains. "It's also a very resonant city, because Richmond represented the aristocratic version of America in the middle of the 1800s. It was at the heart of the culture clash that erupted into the Civil War. And, in a way, it's a place that has been defined by Lincoln more than any other. Springfield, Illinois, is where Lincoln was born, but Richmond is where he changed the nation and made it whole."

Steven Spielberg was exhilarated by the choice. "The city of Richmond completely opened its doors to us and made it very easy for us to come in and tell this story," he says. "There was also a feeling of healing to be able to tell this story in the heart of the former Confederacy."

Doris Kearns Goodwin believes that Lincoln would appreciate the delicious turnaround of having the centre of Confederate power stand in for Washington, D.C. "I think Lincoln couldn't have been happier at the idea that a movie about him has been so warmly embraced by the city of Richmond," she explains. "It's also perfect physically-it's really got that look of the old America in it. This Capitol is able to give that certain feeling of intimacy that a congressional debate can have."

"It really made sense to make the movie here," Rick Carter continues. "There are the battlefields, there's the State House, which from certain angles is amazingly reminiscent of the White House, there are mansions in Petersburg still very much the way they were then, and we were given carte blanche to shoot anywhere, including in the governor's mansion."

The locations were one thing, but creating the interiors with a roughness and liveliness that would give audiences a tangible sense of the times was vital. One of Carter's favourite sets in that regard was Lincoln's office, just down the hall from his living quarters in the White House. He and his team built it, one handmade detail at a time. "I always felt it was very important to have Lincoln's office be as close as possible to the office as we know it to have been," he says, "with all the real colours and textures. We wanted a depth of detail-whether it be in the battle maps, the letters on his desk, the pictures on the walls, or the wallpaper itself-that would re-create exactly the way it was. Of course, the design needed to serve the storytelling, but also to craft imagery that will live on when people want to know what it was like to be in Lincoln's White House."

There was also something more than the period that Rick Carter wanted to convey: "There was a mood and a hauntedness to these halls that Lincoln walked, so there was also something impressionistic at work," he observes.

Richmond's Capitol Building, built in 1788, and designed in the classical style by founding father Thomas Jefferson, made for an atmospheric interior for the U.S. House of Representatives. Though the space is smaller than the actual chamber in Washington, D.C., that worked for the close-in scenes in "Lincoln." "I like the way that it felt jammed because the action amongst the congressmen is so intense," Rick Carter says. "You get a real sense of the friction and debate."

A sense of reality was also essential to the work of costume designer Joanna Johnston, who replicated outfits right out of history. For Sally Field, Joanna Johnston's work was essential. "She is an amazing, amazing artist," says Field. "Almost all of Mary's costumes are incredible replicas of pieces that can be found in photographs and paintings, right up to the final dress you see Mary in while Lincoln is dying. We worked very closely together and it was a wonderful collaboration."

David Strathairn says of Joanna Johnston's work: "She gave us something extraordinary, building the clothes from original pieces that had been preserved. They are clothes that change you and when you see everyone else around you in these relics it takes you into that world. You're really there."

A synchronicity developed between what Rick Carter and Joanna Johnston were each doing individually. Says Kathleen Kennedy: "Joanna Johnston and Rick Carter work together very artistically because of their understanding of the importance of a colour palette. The beautiful costumes that you see Mary or Elizabeth Keckley wearing, with their deep browns and plums, each echo the earthiness of Rick Carter's set design, which together, and in turn, echoes Janusz Kaminski's lighting."

Makeup designer Lois Burwell also immersed herself in research and the character's depths. In working with Daniel Day-Lewis, she was cognisant of just how much President Lincoln was grappling with-and how that showed in his face. "It was an extremely difficult time for Lincoln and when you look at photographs, you can see his decline as if he was going through a battle himself. So we wanted that stress to come out on Daniel Day-Lewis's face. We wanted to give Steven Spielberg his vision of Abraham Lincoln-that texture of the skin and that poignancy in his expression-and we wanted to give Daniel Day-Lewis makeup that would allow him to perform without encumbrance," she summarises.

Daniel Day-Lewis grew his own hair into Lincoln's iconic wavy coif and also his beard, though there was additional painting to shape it to his face in a way similar to Lincoln's best-known photographs. Ultimately, Lois Burwell was able to condense what might have been a 3-hour process into an efficient hour and 15 minutes. Lois Burwell says it worked in part because Daniel Day-Lewis was so fully enveloped in the role. "No matter how skillful the makeup artist, makeup will just look painted on if the actor doesn't embody it," she says. "Daniel Day-Lewis brought so much to the makeup-it was real teamwork."

Meanwhile, Lois Burwell recruited several wig makers, who laboured to keep up with the film's endless strands of head and facial hair, from whiskers to sideburns. Perhaps the most prominent wig of all is Thaddeus Stevens' infamous hairpiece, which he wore because an illness had rendered him bald. Though offered a bald cap, Tommy Lee Jones chose to shave his head to get even closer to the real Stevens in his one fully revealed moment.

All of this attention to detail began to blossom as Steven Spielberg retired to the editing room with his long time associate, Oscar®-winning editor Michael Kahn. For Michael Kahn, the unique task on "Lincoln" would be finding an organic pacing true to the film's quietly mounting emotional power. "We didn't want to rush anything because it's a film where you want people to really listen and understand," he says. "We looked for the moments that give people the time to really look at these characters and think about what they are saying. And this cast is such a pleasure, you can do that."

Weaving the footage into a flowing narrative became one of the most intensive collaborations ever for the two men. "Steven Spielberg wrestled with what to keep and what to let go. These were big decisions because there are so many psychological and political things going on and we were always asking: will this scene echo later on? It was a complex process," Michael Kahn comments.

In the end, Michael Kahn believes "Lincoln" stands out in Steven Spielberg's body of work. "Steven Spielberg admitted he's never made a film with so much dialogue, where every phrase counts so much. We were very conscious of the fact that we had to be right on with the emotions," the editor says. "I think it's one of the best things he's done. It takes characters we've read about in history and makes them alive. You learn about America, about democracy and about what a special human being Lincoln was."

These elements are also reflected in John Williams' score for "Lincoln," a departure for the American composer who has received an astonishing 47 Oscar® nominations and five Academy Awards® in a career filled with indelible music. "For me, this was a very different experience than any of my experiences with Steven Spielberg in past years," John Williams says. "'Lincoln' is more of a musical tapestry, with several very distinct and discreet musical subjects that don't overlap. And in terms of the texture and orchestration, it was also quite different. It's a quiet score with a lot of variation, but also with some broader, noble expressions."

John Williams began with what was the most challenging piece of all-the music that accompanies Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address, as read by Daniel Day-Lewis. "The challenge was to find something worthy of accompanying those great words," he explains. "I started with a hymnal kind of piece and then I kept carving away at it to find the simplicity needed to support Daniel Day-Lewis's delivery, which is itself a work of art."

John Williams began with what was the most challenging piece of all-the music that accompanies Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address, as read by Daniel Day-Lewis. "The challenge was to find something worthy of accompanying those great words," he explains. "I started with a hymnal kind of piece and then I kept carving away at it to find the simplicity needed to support Daniel Day-Lewis's delivery, which is itself a work of art." A potent simplicity would become woven through the entire score. In another key sequence, when Lincoln rides through City Point, Virginia, across a field of broken young soldiers' bodies, John Williams opted for a solo piano. "We didn't want to underscore the bodies on the ground, but just to give a feeling of respect and support a moment of rumination about the tragedy at hand and the challenges of trying to fix things in human affairs," he comments.

Elsewhere, the music shifts with the moment. As Seward's lobbyists head out to finagle votes, John Williams brings in rhythmic, country violins; and as the first African-Americans ever in history enter the House of Representatives, there is a more lyrical moment of full orchestration.

To record this diversity of music, John Williams took the opportunity to work with an orchestra he has wanted to use for a Steven Spielberg score for many years: the renowned Chicago Symphony Orchestra, for whom John Williams has been a guest conductor on occasion. "They are one of the great American orchestras and I've always said to Steven Spielberg, 'Someday we should do something with them.' When we started on 'Lincoln,' Steven Spielberg said, 'Wouldn't this be a great time to work with the Chicago Symphony?' Not only is Illinois the home of Lincoln but Chicago is the centre of the nation, and I think Steven Spielberg liked the idea of bringing energy from the heart of our nation into our film in some way."

Sums up Steven Spielberg: "I've always believed that making sense of the past helps shape our present, helps us figure out where we want go from here. In this way, I think 'Lincoln' could not be more relevant right now. His presidency offers such a vivid model of leadership. He advocated for things we hold dearer now than ever. He stood up for the idea that democracy's survival requires fairness, compassion, respect and tolerance. And sometimes a good sense of humour. That is the soul of 'Lincoln.'"

Steven Spielberg Lincoln Part 1

Steven Spielberg Lincoln Part 2

Steven Spielberg Lincoln Part 3

MORE