Colin Firth 1917

Cast: Colin Firth, Mark Strong, Andrew Scott, Benedict Cumberbatch, Richard Madden, Dean-Charles Chapman, George MacKay

Director: Sam Mendes

Genre: Drama, War

Running Time: 116 minutes

Synopsis: At the height of the First World War, two young British soldiers, Schofield (Captain Fantastic's George MacKay) and Blake (Game of Thrones' Dean-Charles Chapman) are given a seemingly impossible mission. In a race against time, they must cross enemy territory and deliver a message that will stop a deadly attack on hundreds of soldiers-Blake's own brother among them.

"The first time I understood the idea of war was when my grandfather told me about his experiences in the First World War. This film is not a story about my grandfather, but rather the spirit of him"what these men went through, the sacrifices, the sense of believing in something greater than themselves.

"Our two main characters are sent on a dangerous journey through enemy territory to deliver a vital message to save 1,600 soldiers, and our camera never leaves them. I wanted to travel every step and breathe every breath with these boys, and cinematographer Roger Deakins and I discussed shooting 1917 in the most immersive way. We designed it to bring audiences as close as possible to their experience. It's been the most exciting job of my career."

"Sam Mendes

1917

Release Date: January 9th, 2020

Director: Sam Mendes

Genre: Drama, War

Running Time: 116 minutes

Synopsis: At the height of the First World War, two young British soldiers, Schofield (Captain Fantastic's George MacKay) and Blake (Game of Thrones' Dean-Charles Chapman) are given a seemingly impossible mission. In a race against time, they must cross enemy territory and deliver a message that will stop a deadly attack on hundreds of soldiers-Blake's own brother among them.

"The first time I understood the idea of war was when my grandfather told me about his experiences in the First World War. This film is not a story about my grandfather, but rather the spirit of him"what these men went through, the sacrifices, the sense of believing in something greater than themselves.

"Our two main characters are sent on a dangerous journey through enemy territory to deliver a vital message to save 1,600 soldiers, and our camera never leaves them. I wanted to travel every step and breathe every breath with these boys, and cinematographer Roger Deakins and I discussed shooting 1917 in the most immersive way. We designed it to bring audiences as close as possible to their experience. It's been the most exciting job of my career."

"Sam Mendes

1917

Release Date: January 9th, 2020

The Backstory

The Backstory

Before the United Nations was formed, prior to NATO"well before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand set off a chain of events that would draw the world into conflict"nations in the West had primarily acted in their own interests. Never before had countries set aside nationalism for the collective greater good. For that reason, the First World War in many ways unified the West and became the bedrock of modern society.

A global shockwave that made humanity confront our common ground, our joint ideals and shared values, World War I demanded unthinkable sacrifice"calling upon a tested generation's honor, duty and fidelity to country. The impact of the war, and particularly its effect on the young soldiers asked to rise up and defend their homelands, has intrigued filmmaker Sam Mendes since he was a boy.

The idea for 1917 was sparked by stories that Mendes' grandfather, the late Alfred H. Mendes, shared about his time as a Lance Corporal in the First World War, as well as the colorful characters he met during his service. In the year 1917, Alfred was a 19-year-old who enlisted in the British Army. Due to his small stature, the fivefoot-four-inch soldier was chosen to be a messenger on the Western Front.

The mist on No Man's Land"the unclaimed land between Allied and enemy trenches on the frontlines that neither side crossed for fear of being attacked"hung at approximately five and a half feet, so the young sprinter was able to carry messages laterally from post to post. His height meant he was not visible to the enemy, and he literally ran for his life. During the war, Alfred was injured and gassed, and was awarded a medal for his bravery. In his later years, the Trinidadian novelist retired to his birthplace in the West Indies, where he wrote his memoirs.

"I was always fascinated by the Great War, perhaps because my grandfather told me about it when I was very young, and perhaps also because at that stage of my life, I'm not sure I'd even registered the concept of war before," Mendes says. "Our film is fiction, but certain scenes and aspects of it are drawn from stories he told me, and ones told him by his fellow soldiers. This simple kernel of an idea"of a single man carrying a message from one place to another"stayed with me and became the starting point for 1917."

Mendes spent time researching first-person accounts of this era, many of which are held at the Imperial War Museum in London. As he took notes, Mendes began to compile fragments of stories of bravery confronting terror; in time, he began to dovetail them into a single tale.

During this exploration, he discovered that World War I was so wholly entrenched in a relatively small geographic area that it had very few long journeys. "It was a war mainly of paralysis," Mendes says, "one in which millions lost their lives over 200 or 300 yards of land. People are justly celebrated in all parts of the world for gaining tiny sections of land in World War I. In the Battle of Vimy Ridge, for example, they gained 500 yards, but it remains one of the war's greatest acts of heroism. So, the question I asked myself was how to tell a story about a single epic journey, when essentially nobody traveled very far."

His research stalled momentarily, Mendes soon discovered what would become the backdrop for his tale. In 1917, the Germans retreated to what was known as Siegfriedstellung, or the Hindenburg Line. After six months of planning and digging a huge trench system of defenses and deep-lying artillery, the Germans placed a vast number of troops"once spread over the original, much longer, front line"into a new, enormously fortified, condensed line of defense.

The filmmaker discusses how he found the propulsive narrative of what would become his greatest challenge to date. "There was a brief period where, for several days, the British didn't know whether the Germans had retreated, withdrawn or surrendered," Mendes says. "Suddenly, the British were cut adrift in a land they had literally spent years fighting over…but had never seen before. Much of it was destroyed by the Germans, who left nothing of lasting value, destroying anything that might sustain the enemy. Anything of beauty was taken or destroyed; villages, towns, animals, food. All trees were cut down. It was made relatively impassible. The British were alone in this desolate land full of snipers, land mines and trip wires."

Inspired by the fragments of stories from his grandfather, the first-person accounts he had researched at the Imperial War Museum"as well as the idea of the deadly venture to the Hindenburg Line"Mendes crafted the structure of the story that became 1917. "Like most of the war stories I admired, from All Quiet on the Western Front to Apocalypse Now, I wanted to create a fiction based on fact," Mendes says. He reached out to frequent collaborator Krysty Wilson-Cairns, who, unbeknownst to Mendes at the time, is a self-proclaimed "history nerd" and was ideally suited to the material, and their journey began.

Partners in Time

Sam Mendes and Pippa Harris Begin to Build a World

Pippa Harris is Mendes' longtime producing partner at their Neal Street Productions and the two have known each other since childhood. They studied together at Cambridge and have joined forces on many projects through Neal Street, which they run with Caro Newling and Nicolas Brown.

Like Mendes, Harris has a personal connection to this epoch. When she was in her twenties, she edited the letters of Rupert Brooke"a poet who was engaged to her grandmother before dying in the war. "Having edited those letters, I looked in detail at the First World War"at the appalling loss of life, and what it meant for those young men going out who had no idea," Harris says. "I think nobody in Britain at the time had any idea what war was really about. It was the first time that, through poetry and the writings of people on the front, people back home started to have a clear idea of what was actually going on."

Mendes and Harris were rapt by Wilson-Cairns' meticulous detailing and deft ability with character. Building upon their shared history, Wilson-Cairns worked closely with Mendes as they put onto the page precisely what he needed for shooting. Together, they created the saga of Lance Corporals Schofield and Blake, two young men given a seemingly impossible mission: to deliver a message"deep in the heart of enemy territory"that, if successful, would potentially save the lives of 1,600 British soldiers. For Blake, the assignment is deeply personal; his brother is one of the 1,600 men who will die if they fail.

"I wrote a story structure," Mendes says, "Then I brought on Krysty who, unlike me, is used to writing, 'Page One, Scene One,' and not freezing! She took that story structure and put it into script form, and then I spent a hugely enjoyable three weeks rewriting it and then sending it back and forth. After about two months we had a draft, and the final film remains very close to that first script."

Mendes found a dogged researcher in his co-writer, and additional parts of their epic tale were drawn from first-person accounts that he and Wilson-Cairns came across. "I wanted people to understand how difficult it was," Mendes says. "In a sense, the movie is about sacrifice…and how we no longer truly understand what it means: To sacrifice everything for something larger than yourself."

Mendes and Wilson-Cairns had ample resources to draw from. "When Sam and I first started talking about his ideas, I was utterly enthralled; I basically turned up at his house," Wilson-Cairns says. "We swapped a lot of books, as we both had so many. We concentrated on firsthand accounts, on individual soldiers telling their stories and on diaries. There was a lot of that research about the state of play in 1917, as well as an overview of the Hindenburg Line and of that specific withdrawal."

Through weaving a story of two exhausted young men in a terrifying, extreme situation, Mendes and Wilson-Cairns tell a story that speaks of the grit of a generation tested by the atrocities of war. Says Mendes: "I hoped that by looking through the lens of a smaller, human story, told in real time, we might be able to get close to expressing the vastness of the landscape and scale of the destruction. To see the macro through the micro, as it were." Buoyed by their screenplay's real-time countdown, they provide a look inside the journey that countless soldiers took to protect the lives of loved ones…as well as many more whom they did not know, and would never know.

Mendes and Wilson-Cairns had little interest in repeating the beats of previous films. They needed Blake and Schofield's saga to feel urgent, relevant and fresh"and to allow the audience to experience the mission at the same time these two boys do.

The rare opportunity for a young female writer to co-write a war film was one that immensely appealed to the screenwriter. "Sam didn't know this when he called me up," Wilson-Cairns says. "But I've always been interested in the World Wars, and I thought World War I was particularly fascinating and underserved onscreen. I love war movies, I grew up on them and I've always wanted to write one. I seized this chance with both hands and dug in."

Wilson-Cairns found something inherently fascinating about the fact that the global powers of the era seemed helpless to stop the carnage. "World War I was the first war of wholesale slaughter," Wilson-Cairns says. "It was the first mechanical war in a sense that it represented the first meeting of industry and war. What starts with infantry charges and horses quickly becomes a static war fought with tanks, machine guns, gas and planes. So, it was death at an unprecedented level. One of the most extraordinary things about World War I is that, for four years, 10 million people killed each other and at no point did anyone say, 'Enough.'"

Much like producer Harris, what also interested Wilson-Cairns was the way in which stories from the period were told. All society was swept up, including actors, artists, poets and authors. Many years prior to our understanding of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, many did not discuss, privately or publicly, their experience until they returned home, or many years later. The works that were created after the war, alongside the personal diaries of first-person accounts, eventually told the truth of war in a different way, focusing on its devastating impact on humanity.

"The Great War was told and rendered in a very different way from the wars before," Wilson-Cairns says. "It wasn't Kipling's 'The Last of the Light Brigade,' nor was it just surface-level factual reporting. It was poetry and fiction and painting and a vast number of first-person accounts of lived experiences."

As they crafted narrative and dialogue, what struck Mendes and WilsonCairns was the depth of terror that their two young men would have experienced as they attempted to deliver this message across the vast wasteland. "These are moments of real isolation and solitude against huge adversity," Wilson-Cairns says. "You've got snipers, you've got who knows what other dangers in the land and towns beyond. And from just a great story and movie point of view, I think the present-tense action of the movie is mesmerizing."

She admits one of the biggest challenges of penning the film was that, on every single day of shooting, dialogue may have needed to be re-written and quickly finalized. "Because of the nature of 1917, there was no edit," Wilson-Cairns says. "There was no final rewrite. The story and the dialogue was very much set and rooted when we wrapped each day, and there wasn't really any option to change it in post. Literally, after every take, we would pick the favorite take and then match it. There wasn't even the option of using different takes."

Revisiting Hallowed Ground

Revisiting Hallowed Ground

Search for Truth and Memory

As part and parcel of her research, Wilson-Cairns and her mother went to northern France and to the River Somme, locations they found to be extraordinarily poignant. During the almost five-month battle in 1916, more than one million men were injured or died. By the end of the first day of fighting alone, on July 1, 1916, more than 19,000 British soldiers had been killed.

"I went to the Somme and traveled around the areas where this story is set," says Wilson-Cairns. "It was very moving, a staggering amount of death. I went to Écoust, Thiepval [Memorial to the Missing], Beaumont Hamel [which commemorates the sacrifices of Newfoundlanders] and the Lochnagar Mine Crater [largest manmade mine crater on the Western Front, detonated by the British Army's Royal engineers]. You can't possibly imagine the scale of a mine crater. It looks like an asteroid hit; it's so unbelievably large."

The writer knew that to set foot onto these locations was vital to her in her writing of the script. "It helped me understand the scale in a literal sense of the journey the characters would have to take, but also, in a far greater sense, it afforded me the chance to understand the cost, the thousands of young men who died for inches of land," Wilson-Cairns says. "Going there brought it home to me in a way that would otherwise not have been possible."

Likewise, supervising location manager Emma Pill travelled to France, as did Mendes, cinematographer Roger Deakins and production designer Dennis Gassner, to visit the actual locations. They walked through the various trenches that still exist, as well as No Man's Land. They immersed themselves in the vast landscapes, as well as the villages where their characters would have intersected.

As it would not be appropriate to disturb the historical battle zones, filming 1917 in France was never an option. These are sacred places. "Most of the actual sites over there are real battle zones," Pill says. "There's still ammunition that is in the ground. So, we would never have been able to do the amount of excavation that you see here in France. Plus, there are still bodies in the ground. We needed to find a location that we could do the work without disturbing anything historical…or dishonor the fallen."

The only way to find a similar scale of landscape"a place with few trees and no signs of modern life in the United Kingdom"was to travel outside of London and the Home Counties to find open vistas. It was Pill's job to look around the U.K. for locations that matched the scenery in France and discover where sets could be built. Her scouting brought the team to Salisbury Plain, in southwestern England and home to the renowned Stonehenge, to Northumberland, as well as to Glasgow, Scotland, for key sequences set in northeast France, and to Bovingdon in central England for the endless line of trenches.

Ultimately, the film pays tribute not just to World War I soldiers but to all our military members, past and present and their sacrifice for the greater good and pursuit of freedom.

Casting The Leads

Finding Schofield and Blake

George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman

Lance Corporals Schofield and Blake, of the 8th Battalion, have a comradeship and friendship, which in a short space of time is tested far beyond the point of what either could have imagined. Armed with only their kits, maps, torches, flare pistols, grenades and a bit of food, they must cross No Man's Land and find Blake's older brother, a lieutenant in the 2nd Devons. Their orders: head southeast until they reach the town of Écoust, then locate the waiting battalion at nearby Croisilles Wood. Hand the Commanding Officer a letter from General Erinmore and save hundreds of their fellow soldiers from potential death at the hands of the "retreating" Germans. The unexpected, terrifying mission they are sent on changes the course of both of their lives.

When Mendes was choosing the actors to portray these young soldiers, it was crucial to him that audiences experience the story with relative newcomers. George MacKay, supporting player of Captain Fantastic, was cast as Lance Corporal Schofield, and Game of Thrones' Dean-Charles Chapman became Lance Corporal Blake.

"The movie is based around the journey of two young and"at first glance" unremarkable soldiers, and ideally I wanted an audience to have no prior relationship with them," Mendes says. "It was a real luxury, with the unstinting support of the studio, to make a movie on this scale with two actors in the central roles who really are, relatively speaking, new to the game."

In MacKay, Mendes found not only a fantastic young actor, but a performer who embodies qualities he attributes to the hero he and Wilson-Cairns imagined. "There's something about George that's slightly old-fashioned, in that he embodies some virtues"honor, dignity, heroism"that are almost of another time. He feels ageless," Mendes says. "There is also a class element buried in the story. Schofield has a grammar-school-boy quality to him"in this country we would call it 'middle class.' He's been brought up polite, reserved, quite English. But he also has this huge inner landscape. George has immense subtlety, and the skill to convey all those things with the lightest of touches."

MacKay was drawn to those nuances in his character. "Schofield is a quiet man," MacKay says. "He's someone who deals with what he's going through and what happens to him by kind of burying it. He's got a family back home whom he loves very, very much, but because they're not here and because he can't be with them he sort of keeps them completely to himself. He tries to navigate the extremes of what he's living through by keeping himself very levelled, which I found really fascinating to play."

Schofield, in his early 20s, is a veteran of Thiepval, an attack against German forces that proved devastating for British Commonwealth forces. "When Schofield receives the news about the mission he's wary at first," MacKay says. "Schofield is the more experienced solider of the two of them. He's been doing this about a year longer than Blake has. That doesn't make him a super solider or anything, but he's more practiced at all of it. He's a moral man and he understands what has to be done, but he's trying to do it as safely as possible because he's experienced. It's alluded to that he survived the Battle of Thiepval, where soldiers were acting on information that they realised wasn't correct and suffered terrible, terrible losses. He's lost people, he's almost died himself, and he doesn't want to do that again."

So, committed to his character was MacKay that he insisted on doing the majority of his own stunts during filming. One of the few times the production used a stunt double for him was when his character falls backward down the lock-house stairs. "I was afraid he might knock himself out," Mendes says, "which, knowing the level of George's commitment, he would probably have done without a second thought!"

As Schofield's comrade, Blake, the director aimed to cast a young man that could channel the character's innocence and simplicity. "I hadn't seen Dean-Charles at all until he came in and read for the part," Mendes says. "He has a wonderful vulnerability and a sweetness; he's a really good, natural, instinctive actor."

Only 19, Blake is quite good with maps and eager to volunteer for any assignment that would take him back up the line"or even get him more food. "The first time I read the script I just absolutely fell in love with Blake," Dean-Charles Chapman says. "He's this country boy who loves his mom, loves his dog, loves his brother. He's such a lovely, sweet kid that it's pretty much impossible to not fall in love with him."

But when he is selected to pick a fellow member of 8th Battalion and give a vital message to the 2nd Devons, he has no concept of what he is signing them both up for. "He hasn't had much experience with war, at all," Chapman says. "He's only recently just been deployed there. Throughout their mission, Blake is constantly reminded about his family and his brother and missing home, and his desperation keeps him fighting on, no matter what."

Blake's commitment will gradually have powerful impact on Schofield. "Schofield's journey is to save hundreds of men, but it ultimately becomes about saving Blake's brother," MacKay says. "It becomes personal to Schofield. If it weren't for his promise to Blake to complete the mission, I'm not entirely sure he would get there. It's his promise to Blake that keeps him going."

As the film centers on this friendship, and what happens when it is tested to the breaking point, Mendes knew the two young actors had to have an instant connection. "In this war, thousands of men were put together in a situation where class boundaries and generational boundaries were dissolved," Mendes says. "Bonds are made and friendships are created that are sustained for the rest of people's lives. I wanted to find that unexpected friendship between the two men. They like each other and feel a bond, but don't entirely understand why. They help each other, but in ways they don't fully comprehend."

MacKay and Chapman joined the production in November 2018 and extensively rehearsed their parts, along with participating in exhaustive military training. "We did a lot of training, for about five months before we started shooting," Chapman says. "Our military advisor Paul Biddiss talked to us a lot about what it's like to be a soldier, even down to how to salute, how to hold the weapon. We also did some weapon firing with some of the armory guys to get our stances down and to make sure that we knew our weapons inside and out. I even learned how to take a proper bearing with a compass."

It was during these rehearsals that it became clear to MacKay that he was going to need to enhance his personal fitness training before filming began. "Schofield and Blake are literally on their feet for almost the whole film," MacKay says. "There may be only two or three scenes where they actually sit down. In addition, you might do a given run or a walk sixty times in a day. You think about that and you go, 'Oh, god.' You realise pretty quickly that you have to be fit for it, just the sheer physical labor of it."

They two actors also went to the locations for technical rehearsals and spent time in the landscapes they would be traveling through. This gave them a real indication of how it might feel to be pawns in a global conflict, as well as giving them an understanding of what Mendes wanted to achieve with their performances.

"George and I went out to France and Belgium," Chapman says. "We looked at memorials, museums. We even got to walk through some preserved trenches. I gained so much from that trip. I also read a book called The Western Front Diaries. It's just snippets of soldier's diaries, but my great granddad had a diary entry in that book. He had gone into No Man's Land and had been shot through the hip. He laid out there for four days and survived. I read that book pretty much every day before I walked onto set just to sort of get me into the zone."

What attracted MacKay most to the role of Schofield was not only the chance to work with masters of their craft, but the enormous challenge that would be the production. "The movie in itself is a slice of time, and filming was like a piece of theater, every take," MacKay says. "Once it started, it couldn't stop. If something went wrong, you just had to keep going."

Chapman agrees with his co-star. "The camera never ever comes away from these two characters," Chapman says. The actor also appreciated how every single member of his cast and crew had to be at the ready, waiting for the split second when the fickle weather gods would allow for shooting.

"We'd be waiting around," Chapman says, "and everyone would have their eyes up in the sky trying to see how long it would take for the sun to move behind the cloud. But when it all came together, it was pretty thrilling."

For the two young lead actors, the experience of 1917 bonded them in a way they couldn't have foreseen, but that echoes the friendship that is forged between their characters. "It sounds so simple, but at the heart of it all, Dean's just a good man; he's a really good, good man," MacKay says. "I think that's the main thing that Dean has brought to Blake. He's a fantastic actor and shining through all of that is just this … goodness. He incredibly supportive, incredibly caring. Wherever you are with him, whatever you're doing, he's not just there; he's fully there with you. He gives you his focus without even doing it consciously. It's just who he is."

His co-star shares that admiration and affection. "George and I, we went through the ups, the downs, the hard work, the tears, everything, together," Chapman says. "I never once thought that I was on my own with any of it. I love him to pieces."

For both, the making of 1917 had an impact that resonated even beyond the work itself. "The scale of the film is so big, but it's about something so small and intimate, too," MacKay says. "It's about these two men, these two ordinary men who are forced to do this extraordinary thing. You come to know them, and understand them, and that then reverberates out to all the men around them, each, you realize, the hero of his own story. Blake and Schofield could be any other two men, but it's these two men we get to know and that reveals something about all of them"about all of us, really."

The Characters Of 1917

The Characters Of 1917

Because the story is fundamentally linear"these are two men carrying a message to save hundreds of fellow soldiers"the supporting characters are comprised of those whom Schofield and Blake meet on their mission. For those pivotal characters, many of them officers, Mendes needed actors who could generate intensity in the short period of time they were on screen. "You only meet them for five or ten minutes, and then they're gone," Mendes says. "We needed them to bring a sense of history and life lived"to feel like you're intersecting with these other enormous stories that just happen to cross paths with ours. For that, you need actors of authority and status and skill. Many of these actors I had worked with either on stage or on screen before, and I felt certain that they could all create vivid portraits, despite the brief time we spend with them."

Sgt. Sanders

Daniel Mays

"Listen, Erinmore is inside, so tidy yourselves up." When the hardnosed Sgt. Sanders orders Blake to "pick a man and bring his kit," he has no idea two of his soldiers will be headed straight to the Hindenburg Line on one of the most crucial operations of the changing war. "Sanders is your typical Sergeant within the British Army," Daniel Mays says. "He is bullish, battle worn, cynical and very pragmatic. He obviously cares and is in charge of his platoon, and that manifests itself in humor and wise-cracking with his men, particularly with Blake. With any Sergeant, it's about positivity and keeping morale up."

Sanders does know that the Germans are up to something, but he hasn't been made privy to the fact that they have been creating a massive infrastructure behind their new hold. When he does learn what Blake and Schofield are being asked to do, he immediately feels the weight of it. "Sanders' reaction is much like the others, one of total shock and surprise," Mays says. "The enormity and gravity of the mission given to them by General Erinmore is not lost on anyone who hears it. The fate of hundreds of lives is now in the hands of Blake and Schofield, and it goes without saying Sanders wishes them well and wants them to come back in one piece."

General Erinmore

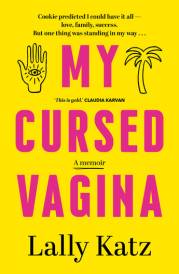

Colin Firth

The weight of the war on his shoulders, General Erinmore tasks Blake and Schofield to make the impossible journey across No Man's Land and find the 2 nd Devons"who are on the verge of advancing at Croisilles Wood in the epicenter of occupied territory. The Lance Corporals' mission: to deliver a letter to Colonel Mackenzie, which demands he call off an upcoming attack on the recently retreated Germans. Few but Erinmore know that the Germans have staged a strategic withdrawal and are now fully prepared to obliterate any troops that challenge them.

"It may be that Erinmore himself privately feels sympathy for the boys," says Colin Firth. "It may be that he doesn't allow himself such feelings or simply doesn't have them. I'm sure he would say that in the end it's all same. The job has to be done.

"All we see of Erinmore is the tactician," Firth continues. "He has, in a short space of time, studied his choice of messenger and deliberately targeted someone who has a deep personal investment in the mission: this young man will want to save his brother. It's a cruel tactic and hard to imagine a more effective one in the circumstances. Erinmore displays a sense of urgency and pragmatism by that fact that he makes the visit to the dugout himself, to give the orders personally and ensure they are understood. Sam was very keen to keep the tone professional: serious, sober and not melodramatic. All we needed to understand is the mission, what is at stake and what must be done. Not how the General feels about it."

After some rehearsal, Firth shot his scene in one day. "Getting the whole scene as a single shot requires a great deal of advance preparation by all departments," Firth says. "For the actors, it's rather like the first night of a play. There is nothing to cover any mistakes. Of course, one does multiple takes, but not endlessly, and one of them will have to be perfect from beginning to end, from every point of view. You can't edit. So, the tiniest slip means that the entire unit has to reset and go again."

Even in his brief time on set, Firth was impressed with the technical precision of what Mendes and his creative team were achieving. "It was fascinating to watch the skill and ingenuity with which the scene was shot," Firth says. "The preparation and skill on display by all departments was pretty staggering."

Lieut. Leslie

Andrew Scott

Now in command of the Yorks division, after Major Stevenson and three of his men were killed two nights prior, Lieut. Leslie is delirious from both the flu and exhaustion with the campaign. Holding the line at No Man's Land, Leslie tells our heroes they are foolish to believe that the Germans have gone and reminds them that the Germans had fought and died over every inch of this land. He asks Blake and Schofield to consider: Why now has their enemy decided to retreat and give the British miles?

"Lieutenant Leslie is a very intelligent character," Andrew Scott says. "His purpose in this story to my mind is to inject a bit of resistance into what might be a straightforward mission, and to show that much of this war was very much a battle of the mind. I think he cares deeply about his men, but he is battle weary, and enormously frustrated. He has to function, and to make decisions while completely exhausted and very sick, living under incredibly torturous conditions. A big challenge for me was to convey that in a few-minute scene, and we tried to accomplish it in whatever ways we could"the tremor of a hand, biting humor, the incredible makeup team, the costumes. When you see this man, you should immediately know the weight of what he's going through."

As with most of the supporting actors, Scott needed to communicate a lot about Lieut. Leslie in a concise amount of screen time. "I worked on the film for two days," Scott says. "This was the third time I had worked with Sam, so it was great to have a sense of the way he works, although, this time around was very different. The best advice he gave me was to relieve myself of the pressure of having to nail it in two or three takes. But it meant that the scene had to work in its entirety on all fronts from start to finish. So, it required a lot of focus. Whether it was about the dialogue, the choreography, the camera and supporting artists, the cigarette lighter lighting at a particular time or being properly engaged with the other actors. There was an enormous amount of pressure because of course we didn't have the reliance on quick edits or pickups. It makes the actor very vulnerable, but conversely makes the actors very powerful, and I think that's where Sam's theatrical background came into play. It was a thrilling way to work and allowed the imagination to run free, which is the most important thing on set I think."

Captain Smith

Mark Strong

When Captain Smith's men happen upon Blake and Schofield at an abandoned farm, the Captain is exhausted and reeling. Wise, insightful and kind, he gives Schofield strategic advice regarding the prickly Colonel Mackenzie: If you do get to him, make sure there are witnesses. Smith knows that some men just want the fight…and are willing to ignore any command given them in order to get it.

Sepoy Jondalar

Nabhaan Rizwan

One of Captain Smith's men, with whom Schofield hitches a ride to get as close to the new line as possible, Jondalar is a Sikh Private who defies his fellow soldiers' open prejudice and amuses them with spot-on impersonations of senior officers. Only last night, did Jondalar's unit cross No Man's Land just outside Bapaume, and the private is rightfully suspicious of just how cunning their German foes can be.

Lauri

Claire Duburcq

A brave young woman whom Schofield encounters in a battered hovel in the town of Écoust, Lauri tends to his wounds while enlisting his help in securing nourishment for an abandoned infant left in her charge. "Lauri doesn't represent a territory or a nation, but she represents life, which is full of fragility in the hostile ground of war," Claire Duburcq says. "I have a great grandmother who is 103 years old. She has always told me that during war, we lose everything. I think Lauri has lost everything. All her bearings. But she is a survivor. She doesn't have a choice but to stay hidden because since Germany invaded France, soldiers have become omnipresent."

Initially unwilling to trust any soldier, Allied or German, the teenage Lauri instinctively senses that Schofield is one of the few people she's encountered in this endless war who will help her. "She can't trust any soldier because they are all armed," Duburcq says. "She can't see a difference between a German soldier or an English soldier because they all represent violence and any armed man has power over her life. She is guided by her instinct. She's alive because of her humanity, and she shares that with Schofield. When everything else is lost, Lauri's instinct drives her to repair the living people, because if she can live, she can help others live as well."

Lieut. Richards

Jamie Parker

Commanding officer of 2nd Battalion, A Company, Lieut. Richards leads the men who will serve as the first wave into the recently redrawn No Man's Land southeast of Écoust. "In the glimpse we have of Richards, he seems, in the best way, anonymous," Jamie Parker says. "Not a man in a set of clothes, but a duty being performed by a ranking officer. That example would, I imagine, gain him respect from the men, who see him there right in the same boat as them. If I were one of his men, I imagine I'd have no alternative but to trust in the notion of order Richards is trying to maintain amidst all that chaos."

At the edge of No Man's Land, Richards keeps his focus on his duty. "I can't comprehend what it must have been like to be in No Man's Land," Parker says. "Richards' attention is on the job"focusing on that, I imagine, is what keeps him going. It doesn't allow room for his own thoughts. But the long stretches of quiet inbetween the action, as I understand it, are when the dread gnaws away at selfcontrol. For some men in the story, that process is already so complete, it's rendered them effectively useless in action. But for Richards, by the time we see him at least, he still seems able to lose himself in the task at hand."

When Richards tells Schofield that Colonel Mackenzie is 300 yards further up the line"in a cut and cover"Richards cannot believe his eyes when he witnesses what the Lance Corporal is willing to do next. "Richards' focus is broken by Schofield, and if he had time to contemplate Schofield's message, I think he might just be as destroyed by the cruelty of that timing as it's possible for a man to be," Parker says. "But the vein Richards is in means that his first thought is not for himself, but for the sake of others who will shortly come after him. That's why he tries to stop Schofield making that decision."

Major Hepburn

Major Hepburn

Adrian Scarborough

Chief among Colonel Mackenzie's senior officers, Major Hepburn is ready to give the word for Devons, B Company to advance on the German soldiers that Mackenzie believes are outgunned and on the run. Prepared to send in wave after wave of his men over the top, Mackenzie thinks victory is 500 yards away…yet even he cannot be certain about defying a new Army Command.

Lieut. Blake

Richard Madden

Lance Corporal Tom Blake's brother, Lieut. Blake is a proud officer in the Devons, A Company and he has followed Colonel Mackenzie to the brink of the Hindenburg Line at Croisilles Wood. He has no inkling that his younger sibling has been tasked to stop his mission. Like his commanding officer, he is uncertain what's behind the Germans' new blockade: a three-miles deep arsenal of destruction"with field fortifications, defenses and deep-lying artillery"the likes of which the British have never seen before.

Colonel Mackenzie

Benedict Cumberbatch

In command of 2nd Battalion and leading the march toward Croisilles Wood, Colonel Mackenzie is convinced that he has the Germans on the run and can break their lines. Potentially ignoring incoming orders to stop the attack, Mackenzie is positive that his newly unauthorized mission will turn the tide of the war. Yet, General Erinmore is certain that the Colonel, who has ceased all contact with his command, is ill-informed and outgunned.

Crowd (Background Actors)

Unlike most films that entirely use digital extras for crowds, the background actors in 1917 were real men, just like the husbands, fathers, brothers and sons that fought the actual war. Mendes selected the film's 500 supporting artists personally from an initial group of 1,600 recruits by the production team. The film's military advisors put them all through boot camp, which included teaching them about battle tactics, aggression and weapons handling.

A huge number of the men who served in World War I were quite young, and in some circumstances, there were boys under the age of 16 who lied about their age to sign up. For the scenes that required crowds, extras were cast in the London area for the Bovingdon portion of the shoot. For Salisbury, due to the long period of filming in the area, local men aged between 16 and 35 were invited to attend open casting auditions.

These auditions took place in February 2019, when crowd second assistant director Eileen Yip and Holly Gardner of Two 10 Casting saw 1,600 men over two days of open auditions. A certain level of fitness was required, as the men needed to be able to run long distances while carrying weapons. Many of those selected were asked to grow moustaches and no beards were permitted"apart from for the Sikh soldiers"who also wore turbans.

In sum, 500 extras were cast for the scenes in Salisbury. Some of the extras from Bovingdon enjoyed their time on set so much that they travelled to Salisbury as well.

The Cinematography and Editing

Immersive, Visceral, Continuous

How 1917 Was Lensed

Mendes' vision to capture the story in real time in a way that plays as one continuous shot requires the audience to join the characters and immerse themselves in their turbulent journey. To be clear: 1917 was not shot in one take, but was filmed in a series of extended, uncut takes that could be connected seamlessly to look and feel as if it is one continuous shot. As there is no cut within a scene, the viewer, much like Schofield and Blake, is not able to step away from the mission that lies in front of them. Although Mendes had shot the opening scene of Spectre as one continuous shot, shooting an entire film this way was a new experience for everyone, including Mendes. "I've never been in a situation where we'd start shooting on Monday, and I knew for a fact that what we shot on Monday would be in the movie," Mendes says.

Shot in this way, the audience gets an authentic, tangible sense of what these boys would have gone through. "The reason I chose to do that with this material is, from the very beginning, I felt it should be told in real time," Mendes says. "The sense of distance traveled is very important. But it is also, most importantly, an emotional decision, that I hope connects you even more closely to the journey of the two central characters. I wanted an audience to take every step of the journey with them, to breathe every breath. It wasn't a decision that was imposed on the material afterwards. I had the idea alongside the idea for the story – style, form and content all came at the same time. You begin to construct the narrative so that every second forms part of one continuous, unbroken thread."

Mendes and Academy Award® winner (and 14-time Oscar® nominee) Roger Deakins worked with one another on Jarhead and have collaborated on films from Revolutionary Road to Skyfall and have a shorthand with each other. "From the first moment I talked to Sam about the idea as a one-shot movie, I knew it was going to be immersive and that it would be essential for the storytelling," Deakins says. With the one-shot premise, it was imperative to block the scenes during 1917's four-month rehearsal process, and to discuss the layout of the sets in great detail. Once it was established how the actors would move within the space for the scenes, it became possible to map out exactly where the camera would move. The cinematographer expands on this process. "Sometimes, you need to be close, and sometimes you want to pull away and see the characters within the space, within the landscape," Deakins says.

"So, it was getting a balance between that. A lot of the blocking was done in our heads, then Sam would rehearse the scenes, then we drew schematics and had a storyboard artist who gave different options within those basic ideas. It gradually evolved, but then when we worked with our actors on location, it evolved even further."

The director reflects that with standard filmmaking, there's always a "get-outof-jail card" that allows fixes and changes in post. "Your normal thought process is, 'We might be able to cut around this moment, or shorten this scene, or we might take that scene out altogether.'" Mendes says. "That wasn't possible on this film. There was simply no way out. It had to be complete. The dance of the camera and the mechanics all had to be in sync with what the actor was doing. When we achieved that, it was exhilarating. But it took immense planning, and immense skill from the operators." Deakins often needed to be with the focus puller and DIT in a small white van, remotely operating the camera even if it was being carried. As they were frequently operating the camera remotely across vast distances, it was very tricky. "Sometimes, we'd have a camera that was carried by an operator, hooked onto a wire," Mendes says. "The wire would carry it across more land. It was unhooked again, that operator ran with it then stepped onto a small jeep that carried him another 400 yards, and he stepped off it again and raced around the corner."

Due to the prep period and many lengthy rehearsals on shooting days, there was always a clear starting point and physical structure to the scenes, but this did not mean the filmmakers and cast were fixed entirely in their approach.

Because the film needed to play as one shot, primarily filmed outside, Deakins relied upon light that was as natural as possible, which meant Mother Nature was as much in charge of the shoot as the filmmakers were. Instead of blue skies and direct sunlight, which bring with it shadows that are difficult to shoot around and impossible for continuity, the production prayed for the days to be consistently overcast.

No location ever repeats in 1917, so the camera is constantly moving through landscapes. "Being such an exterior movie, we were very dependent on the light and the weather," Deakins says. "And we realised, well for a start, you can't really light it. If you were running down a trench and turning around 360 degrees, there's nowhere to put a light anywhere. Because we were shooting in story order, we had to shoot in cloud to get the continuity from scene to scene. Some mornings the sun would be out, and we couldn't shoot. So, we would rehearse instead."

For the director, total engagement from all involved in his production was paramount. "That is behind the way in which we decided to shoot 1917," Mendes says. "I wanted people to understand how difficult it was for these men. And the nature of that is behind everything."

His comrade in arms shares that the film must be experienced to believe. "Until you actually see this on a screen," Deakins says, "you don't really realize how immersive it is and how this technique draws you into it."

Fresh from the Manufacturer

Deakins Wields the ALEXA Mini LF

Deakins has long used ARRIFLEX cameras on his productions, and during summer 2018, he and James Ellis Deakins (Sicario)"his wife and digital workflow consultant"went to ARRI Munich and discussed a mini version of the ALEXA LF camera that could deliver the intimacy and speed Mendes required of the shoot. ARRI advised that it was in the process of developing one, and the couple asked if the manufacturer could have it ready by 1917's start of shoot: April 2019.

Once the ALEXA Mini LF prototypes proved ready, from February 2019, Deakins and his team ran camera tests with the ALEXA Mini LF. They tried it out with a variety of rigs they wanted to use during filming"including the Trinity, Steadicam, StabilEye, DragonFly and Wirecam.

Just in the nick of time, 1917 would be shot on the brand-new ALEXA Mini LF with Signature Primes in combination with the Trinity Rig. The camera has a largeformat ALEXA LF sensor in an ALEXA Mini body.

Especially for use on this epic, ARRI Munich had three cameras ready early. The size of the cameras was ideal for the epic film, as well as its large-screening format. Officially launching in mid-2019, the ALEXA Mini LF expands ARRI's largeformat camera system. At the time, the 1917 production had the only working ALEXA Mini LF cameras in the world. ARRI had released only the large version of the camera a year earlier, in 2018. Says the manufacturer: "ARRI's large-format camera system is based around a 4.5K version of the ALEXA sensor, which is twice the size and offers twice the resolution of ALEXA cameras in 35-mm format. This allows the filmmakers to explore their own take on the large-format look, with improvements on the ALEXA sensor's famously natural colorimetry, pleasing skin tones, low noise, and suitability for High Dynamic Range and Wide Color Gamut workflows."

Invisible Edits

How to Cut a Film with No Cuts

The challenge of joining the cuts in 1917 is that every scene had to be shot with incredible precision…so that two frames could be blended together seamlessly on screen. That painstaking attention to detail added another layer of continuity because the pacing needed to match, as well as other elements in the scene, such as the weather, cast and sets.

As it was crucial for the takes to be tracked, it meant fully focused attention" and constant vigilance"from the script supervisor, visual effects and the editor. It was imperative for Mendes, Deakins and their fellow Oscar® winner, editor Lee Smith, to know the moment at which the shot would be stitched from one scene to the next, as it could never be fixed in post with a cut to a different perspective.

In order to take the characters seamlessly from one cut to the next, Mendes made sure that blends happened in a variety of subtle ways. That could mean traveling through doorways and curtains, or when the characters enter a bunker, or with a silhouette, or a body movement, or a foreground element or a prop…or even a 360-degree shot.

Producer Jayne-Ann Tenggren walks us through the logic. "How we blended from one shot to another was designed around the action, sometimes because of a change in lighting environment, sometimes because of a need to change the camera rig, and sometimes simply an emotional choice as to how long the scene should run," Tenggren says. Lest you believe editor Lee Smith had it easy on the production, think again. "This has been a very complicated film to edit because the whole process of the blending, making it look like one shot"and doing the kind of the mixing of those shots"is so crucial, and has had to be done so fast, in order to give Sam instant feedback," producer Callum McDougall says.

"In the opening of Spectre, we created one long shot in Mexico City. But it's nothing compared to what Lee, who's our same editor, has had to do here."

For Mendes, this production has been an embarrassment of film-artist riches. "We have Roger Deakins," Mendes says, "who you could argue is one of the two or three greatest living cinematographers, fresh off his Oscar® win for Blade Runner 2049, collaborating with Lee Smith, who just won the Oscar® for editing Dunkirk, and Dennis Gassner, who I've worked with five times now. We started working together on Road to Perdition way back, and he also designed Blade Runner, Skyfall and some of your favorite Coen brothers' movies."

The Pre-Production

Steps of the Journey

Departments Work As One

Mendes would not have been able to consider shooting a movie in such an unusually daring way without the steadfast support of his core group of collaborators, many of whom he had known for decades. As a great number of the crew had worked together previously, there was an easy camaraderie and shorthand. This symbiosis would prove beneficial, as all departments needed to be fully prepared before stepping onto the sets. In fact, 1917's intense rehearsal process was quite similar to the preparation of a piece of theater.

Producer Jayne-Ann Tenggren has worked with Mendes for more than 18 years, and 1917 marks the third time that producer Callum McDougall and coproducer Michael Lerman (Spectre) have collaborated with him. For cinematographer Roger Deakins, this is his fourth outing with the director, while 1917 marks production designer Dennis Gassner's fifth Mendes collaboration.

Makeup and hair designer Naomi Donne, production sound mixer Stuart Wilson, supervising location manager Emma Pill, stunt coordinator Benjamin Cooke and editor Lee Smith have all worked with the director before, and composer Thomas Newman has created the scores for six prior Mendes films.

Joining Mendes for the first time are costume designers Jacqueline Durran and David Crossman, casting director Nina Gold, VFX supervisor Guillaume Rocheron (Life of Pi) as well as set decorator Lee Sandales, prosthetic designer Tristan Versluis and SFX supervisor Dominic Tuohy.

Mendes reflects that what made 1917 differ from any other movie he has made is the way in which his entire team constructed it. Mendes says, "It was such a unity. The collaboration between heads of department and my main collaborators was daily, and started much earlier in the process than ever before. We rehearsed for seven or eight weeks on and off location. Everyone was involved and continued to be involved throughout the shoot. That's very moving when you see such great artists at work, all as equals, with immense mutual respect, and very little hierarchy."

Rehearsing World War I

Although all films require preparation, the prep period for 1917 was even more important than on conventionally shot films. In fact, it was paramount. The technical demands of how the epic would be shot meant that every step of the journey had to be timed precisely during rehearsals.

Mendes admits that the challenges of prepping were the challenges of getting ready for a normal movie…times five. "You have all the things you normally have to do," Mendes says, "but here we simply had to work in much more detail. For example, we had to measure every step of the journey. It's fine to write, 'They walk through a copse of trees down a hillside, through an orchard, around a pond, and into a farmhouse,' but the scene had to be the exact length of the land. And the land could not be longer than the scene! We had to rehearse every step of the journey, every line of dialogue on location."

The level of detail called for Mendes, MacKay, Chapman, Deakins, Gassner, supporting cast, key creatives and team members to rehearse not just on location, but on a huge soundstage at Shepperton Studios. There, they marked out on the floor the dimensions of the sets for each scene. Every step of the journey was rehearsed in this space. "We were in this massive room, the rehearsal room, with all these cardboard boxes stacked up around us to sort of map out the set shape," Chapman says. "Sam already knew exactly how the blocking should look, but sometimes we'd come across something that didn't sync right or didn't look right. When that happened, Sam would just stand there, he'd close his eyes, think about it, and then just solve it. I've never seen anything like that. His ability to do that was amazing."

Next, they went out on location for tech rehearsals. "This world had to be crafted around the rhythm of the script," Mendes says. "You can't just jump 100 yards in a cut. If your location is 100 yards too long, you're not going to have the scene that lasts the journey; the two things are obviously interlinked. That made the prep much more complicated than normal. In many ways, it was more fun, because we had to do it very early and walk the land, and physically feel the reality of their journey. Then, we had to discuss and test the camera movement and positioning for every moment of every scene, long before we shot it."

As well as storyboards, a schematic document of diagrams was created to accompany the script. This mapped out where each character was moving at any given time, as well as exactly where the camera would be during any given scene" and in which direction it would be pointing.

By the time prep was finished, producer McDougall was confident that his team was more than up to dealing with the myriad complexities of the shoot. "When you have a film as well-prepped as we were"and with the expertise of the people we've engaged"with our locations, production team, special effects and other departments, we knew that whatever would be thrown that we were able to handle," McDougall says.

During prep, Deakins and his crew were working on the camera moves and how they would be able to complete a shot without cutting"all while constantly moving. At times, the camera would need to seamlessly interchange"using a variety of rigs during a take, which could involve a Steadicam operator, followed by a wire cam and back to the operator on foot or on a vehicle.

One of the biggest challenges of production was that they were unable to employ long-familiar tools. "We're used to having coverage and cuts and camera placement to tell a story," Mendes says. "We can normally change the pace in editing. We can tweak performances, timing, rhythm, dialogue. That is the language of film. You can cut to a wide shot to establish geography for example, or you cut to a close up and push in to feel connected to a character. We didn't get to play with any of those tools with 1917, yet we still had to do all of those things."

Getting Soldier Ready

Ex-paratrooper Paul Biddiss (Jason Bourne), the film's military technical advisor"who served in the British Army for decades"put the main players through their paces. To get them into the mindset of a soldier, he began their training with extensive marching. Biddiss explained that once his men were in a uniform, there were rules about what was expected of them. They were also taught the importance of looking out for fellow soldiers, as well as bonding and friendship.

In Bovingdon, prior to the start of shoot, there was a boot camp to prepare the actors for the scenes filmed there. As these were more sedentary, the purpose of the camp was to learn primarily about trench life. The follow-up Salisbury boot camp required more detail about tactics and aggression, as the crowd selected for this trench-run scene was required to be more physically robust.

"Contrary to popular belief, the soldiers of World War I didn't just get out of a trench and run like a bunch of banshees towards the enemy," Biddiss says. "They had section objectives. We needed to teach our performers how to move in sections, under their section commanders, as well as how the Lewis gunners and the Vickers gunners would operate to cover arcs."

The main cast and crowd were taught weapons handling and safety, plus how to wear their webbing"how it is fitted, and from the rounds and the masks to the water pouches…what equipment goes where. Biddiss also made a point to emphasize with the importance of foot care with the principal cast. "It was the first lesson I taught them," Biddiss says. The main cast, like actual World War I soldiers, were not used to working in military boots, so the lessons helped them avoid blisters from all the leg work required of them each day.

George MacKay found all of it invaluable. "Every time we'd do those rehearsals Dean and I would put on the boots and the webbing, and work on just really simple things like taking ammunition out of a pocket," MacKay says. "The first time we did it, we were all fingers and thumbs. Or we'd kneel, and all of our ammunition would fall out. We were just really green in the beginning, but little by little, day after day, it becomes second nature."

The production also engaged the expertise of military historian Andrew Robertshaw (War Horse), a former Military of Defense civil servant who spent many years excavating trenches and mine craters in France and Belgium.

Robertshaw and Biddiss worked closely with Joss Skottowe (Spectre), ex-military supervising armorer, and stunt coordinator Benjamin Cooke with the main cast and crowd. The roles complemented one another"from explaining the intricacies of the war, to the requisite soldier behavior, through how to load, fire and reload weapons and apply dressings, in addition to how to approach the reality of going over the top and all it might entail…

The Shoot

Margins for Error

Margins for Error

Fulfilling Mendes' Mission

Implementing Mendes' painstaking plans meant ensuring a viable frequency range was maintained to get the video and sound back to the director on his monitor. As mentioned earlier, Deakins was often stationed with the focus puller and DIT in a small white van, remotely operating the camera even if it was being carried, frequently operating the camera remotely across huge distances.

During takes, Mendes was in a customized "horse box" with co-producer/first assistant director Michael Lerman and script supervisor Nicoletta Mani (Mission: Impossible-Fallout). Producers Harris and Tenggren, along with writer Wilson-Cairns and video operator John 'Jb' Bowman (Skyfall) were alongside the director in another small trailer.

Due to the nature of the 360-degree shoot, those crew whom would normally be behind the camera often could not stand alongside the set. A small group of key crew would place themselves in a safe spot and all others, including the tech trucks and support, were based much further away. On occasion, it was not possible to keep everyone far enough away, which meant that, in post-production, VFX would need to paint out whatever should not be in the frame.

Directly outside Mendes' horse box was a large black rehearsal tent for playback. This allowed him to talk through the shot with the actors and Deakins, as well as other key head of departments.

It was difficult to have a normal video village set up, as well as sound and checks areas for makeup and hair, costumes and other departments. Another large tent was set up with monitors and chairs to accommodate these crew members.

The need to be in sync with the actors and the complexity of the camera movements meant there was no margin for error. Not only in prep was it vital to rehearse, but also on every single day of filming. Mendes, the actors, Deakins, the camera team and the rest of the crew would rehearse for a large part of the day" until the light was ideal and everyone was primed and ready for the take. While that might sound a bit draconian, Mendes was quite mindful that, regardless of the planning, what he hoped for"however much he conceptualized" was that the team embraced what could happen when they were all discovering the undefinable. "If it had just gone to plan, in a way I'd be disappointed," Mendes says. "What was exciting was when it went to plan…and then something unexpected happened. As in all moviemaking, you always hope for happy accidents." Mendes says, "It could be a look, a way the light falls or something that somebody accidently says on that particular take…and it ends up in the movie. No matter how much you imagine a scene, it can never stand up to the reality of actually doing and seeing it. Part of the job was to leave myself available for moments of inspiration, accidents or unplanned changes. You get to a certain point where what you want to see is the shot you'd imagined. You get it, and then you have to sit back and say, 'Yes, we've got that now… but is it enough? Could there be other things happening we haven't conceived?' In almost every case, the answer was 'Yes.'"

The Production Design

Marrying Script To Mileage

Designers Lead The Charge

As the majority of Mendes and Wilson-Cairns' screenplay exists in the exteriors, and no location through which the two principal characters move repeats on screen, the enormity of the challenge in front of Oscar®-winning production designer Dennis Gassner and his colleagues was obvious to all involved. With the landscapes came the inescapable and unpredictable British weather.

Because the story is linear, the weather needed to consistently match from scene to scene. While the production could control many aspects of the shoot, weather would never be one of them. Armed with a Farmer's Almanac and weather.com, Gassner examined multiple weather forecasts"from long range to daily and hourly. At the mercy of the sun, clouds, rain, sleet and snow, the indefatigable crewmembers crossed their fingers and said respective prayers every night before the next shooting day. "You've never seen a group of people so happy for bad weather," George MacKay says. "You get a bit of cloud of and everyone will be like, 'Okay, let's go!' We're going to get two shots today!'"

Gassner has known Mendes for two decades and Deakins for three and offers that their shorthand was the only way they could accomplish so much in such a period. "I needed to build the world, Roger needed to light it, and Sam needed to take us on the journey," Gassner says. "That connection among the three of us was wonderful. We all did our jobs in the best way that we were possibly able to do." The production designer extends the kudos to his fellow crew. "Everybody on the production was so engaged," Gassner says. "I've never seen a film crew that bonded together in such a strong way. It was technically really hard work. That focus kept driving us forward to see what we were going to get. We got through this because of all of our experiences…and a tremendous amount of luck."

Weather, Research and Planning

Although the weather occasionally presented challenges, for much of the shoot the cast and crew of 1917 were blessed with dry, overcast days, crucial to the matches that director of photography Deakins and editor Smith needed for scene continuity. The not-so-flexible schedule of 65 days had little weather cover inherent within. This meant Mendes' production was to be almost completely exposed to the elements…for the majority of the time that was allotted to shoot.

Due to the duration of time at the locations, planning permissions and numerous surveys were required for the building of sets. It was a massive undertaking for supervising location manager Emma Pill and her locations team.

The unpredictable weather and constant movement on location created major obstacles for the filmmakers, cast and crew, which they had to collectively overcome. No stranger to lensing in the most complex of environments"007 films are no joke" their captain had to take the elements in stride.

"Every location brings its own set of challenges," Mendes says. "Whether you are shooting on land, shooting someone being carried down a river without being able to cut"or traveling large distances through nighttime landscapes at great speed"these are all immense challenges in different ways. Even if the weather is perfect, each challenge has its own particular degree of difficulty."

Thanks to the extensive preparatory period, Gassner and his team carried out a fastidious amount of deep-dive research. Inspired by the meticulous script, his crew delved into archive material, photographs, art and other material from the era.

As drawings, concept art, plans and set models evolved, the art department found Mendes' rehearsals quite valuable. They allowed them to precisely plot out the sets before they broke ground for the actual set builds. "It was all about planning," Gassner says, "as well as the choreography, marrying the script to the mileage"to how far we were going to have to go, step by step. It was an amazing amount of work, and I have to say that I enjoyed it the whole time."

Scouting

Pill and her team had the mammoth task of scouting multiple, massive-scale locations at the same time other locales were being prepped, built upon, filmed on and then struck…all over the country. "In Salisbury, we had the opening of the movie and the opening trench," Pill says. "We're then at Bovingdon, where we had the second-line trench moving into the frontline one. We also had No Man's Land, which took us into the German trenches."

When not building "underground" sets for the German dugout at Shepperton Studios"or the German tunnel set that was constructed in a Salisbury barn"Pill was dealing with an Oxfordshire location, which served as a large quarry that brings Blake and Schofield out of the enemy's tunnels and into an abandoned ammunition site. "That then leads us to Salisbury Area 8, which takes us from a copse down through a built French farm set, which takes us up a hill on a convoy route that takes us to another location in Salisbury," Pill says. "This is called Tinker's Track, which takes us to the canal in Glasgow…which takes us to our backlots at Shepperton."

That still wasn't all. "That then takes us to a river in County Durham, where we used a location, which is a white-water rafting center in Stockton-on-Tees," continues Pill, "which then takes us to the woods, Salisbury Area 14." Quick pause... "Which then brings us out onto the final battle here, and then takes us back to Area 2 at Salisbury for the end of the movie."

Building Trenches

One of four art directors under the production designer's supervision, Elaine Kusmishko (Beauty and the Beast) was responsible for all trenches used in 1917. From the Western Front where we meet Schofield and Blake to the trenches held by Colonel Mackenzie.

Developed in central England, at Bovingdon, the almost-mile-long of trenches were dug and dressed with great attention to detail. "This location was chosen because of the duration of time that we could have the area," says Kusmishko. "We had the frontline trench, which automatically leads into No Man's Land, which we needed to show as a continuous set. That was quite a bit of land, especially flatland that was required."

Out of historical accuracy, the team's German trenches were built quite a bit wider than the Allied ones. Essentially, the enemy was there to stay. "They always thought it was going to be a long-term war and bunkered in," Kusmishko says. "They fortified their areas with concrete shoring and they really worked on their trenches. The Allies basically showed up and thought they were going to just take ground straight away; they believed they'd move forward and advance on the Germans. They never realized they were going to be there for so long."

All that painstaking attention to detail had a profound impact on the actors during filming. "George and I were standing in a trench on set in Bovingdon, the rain was coming down really hard, and we were just waiting for it to pass," Dean-Charles Chapman says. "In the trenches there's not much cover at all, and while we were standing there, George tapped me on the shoulder and pointed beyond me to the background actors. They were all in their uniforms, and they were all trying to get under this tiny bit of metal from the trench. I remember looking at that and thinking, 'That is exactly how it would have been 100 years ago: these men just waiting, bored, cold, trying to get cover from the rain.'"

Dressing

Not to be outdone by a locations manager that eschewed sleep for several months or the four art directors, set decorator Lee Sandales and his team sourced nearly all the dressing seen in 1917. "Much of it was made, like our German guns, which were in the quarry set," Sandales says. "We also had to make 6,000 shell casings for that set, as well as all the defensive gates, which were then covered in layers of barbed wire. We also had to research, find and purchase a lot of the set dressings for the rest of the production. We traveled to multiple markets up and down the U.K. and to the south of France and Paris to build up enough stock."

The Locations

From Scotland to Southwest England

Locations of the Epic

Shot across the U.K., 1917's locations included Govan docks in Glasgow, Scotland, the River Tees in North England, a disused quarry in Oxfordshire, Bovingdon Airfield in Hertfordshire and Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, where the Ministry of Defense owns 94,000 acres of land. In sum, during production, the length of trenches dug at Bovingdon and Salisbury were an astonishing 5,200 feet (approximately one mile).

Bovingdon, Hertfordshire

Bovingdon Airfield was chosen for its proximity to Shepperton Studios and the vast size of the site (60 acres). The height of set builds had to be taken into consideration due to a National Air Traffic Services radar station in an adjoining airfield. The art, construction and greens departments arrived in January 2019 to commence prep, and the site was returned to its original state and handed back by locations in early September. The Bovingdon trenches were clay, and approximately 2,000 feet (610 meters) of Allied trench was built at this location across both fields.

The Allied Trenches

To design the frontline trenches, the art department undertook a great deal of research and discovered many Allied trenches with different construction techniques. The frontline trenches created were almost all similar in width to the ones in which the soldiers would have been fighting during World War I.

Primary considerations were safety and drainage. As the trenches had 15- degree angles, shoring was required. The earth walls were retained with posts and boards to prevent collapse. In addition, a combination of materials was used to cover the framework and finish the look.

These included textured, painted timber, plastersheeted earth, corrugated iron and sandbags. Wire mesh- and wattle-fencing were aged, and the paint team had a separate crew who would travel down the trenches" with axes chains and hammers"to establish the requisite four-year-old look.

No Man's Land

No Man's Land's set was split into two sections. There was the main section from the "up and over" to the far side of the large shell crater. There was also a repeat of a small section of the back rim of the large crater to the German frontline trenches. It became a vast, bleak landscape with deep mud and craters, barbed wire and the dead bodies of soldiers and horses. Due to its open nature, the entire 360- degrees of the set had to be scanned by the VFX team for additional use.

German Trenches

The German Trenches differed from the Allied ones in many ways, but primarily in size. During World War I, these trenches were dug deeper and wider. In addition, different materials"such as concrete and constructed-timber shuttering" were used to reinforce. The Germans also created vast trench systems and dugouts much deeper and more extensive than the Allied ones. This meant they were better able to protect and support their troops during key periods of being dug in. The length of the German trenches here was approximately 330 feet (100 meters).

Ambrose Quarry, Oxfordshire

Ambrose Quarry is owned by Grundon Sand and Gravel Ltd. Founded in 1929, it is one of the leading suppliers of sand and aggregates in the U.K. for construction, landscaping, decorative and leisure markets. The set was vast and chalky and served as the location where Schofield and Blake exit the German dugout after an explosion. The lance corporals find huge guns that the Germans have destroyed, as well as empty shells littered across the quarry.

Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire

Salisbury Plain was chosen because of its wide-open landscape, one that could pass for France. Most open landscapes in the U.K. are either open-moorland or dominated by hedge lines, stone-walling, villages and transmission towers, but not Salisbury Plain.

Filming took place in Wiltshire, which is in southwest England, covers 300 square miles (775 square kilometers) and stretches into Hampshire and Berkshire. It is a system of chalk-down lands with grassland, arable farmland and areas of trees. Salisbury Plain is famous for its archaeology, including the world-famous Stonehenge. A vast part of the plain has been used by the British military for training purposes for more than 100 years. Therefore, much of the land remains in a natural state. In certain areas, as far as the eye can see, there is little to no evidence of modern living.

Planning permission was required for the set builds and"due to the sensitive nature of the area"ecology, archaeology and geophysical surveys were required. Daily during prep, shoot and strike, locations had to liaise closely with the military as well, due to it being near a live-training site.

The construction department commenced excavation at Area 2 at Salisbury in late February 2019, with the work ongoing up until filming took place. This trench was chalk, as opposed to the Bovingdon clay one. Still, the Area 2 trench was constructed in the same manner as Bovingdon's, using the same materials.

The French farmhouse, barn and the other outbuildings were built in workshops at Shepperton Studios and then transported. Plaster sheeting and spreading, aging of timbers and painting finishes were all carried out on site. Once the set was complete, it looked like the farmhouse, barn, outbuildings and orchard had been there forever.

Area 14 was chosen as a location due to its landscape and topography. The combination of the copse that leads out onto a rising hillside was just what Mendes required for the scenes where Schofield reaches the 2nd Battalion frontline trenches. The quantity of chalk and top soil excavated from the site to create the trenches measured approximately 1,615 tons. The length of the trenches dug at Area 14 was approximately 2,500 feet (762 meters). For each trench-run take, the SFX pits exploded approximately 35 tons of material into the air.

Govan Graving Docks

River Clyde, Glasgow