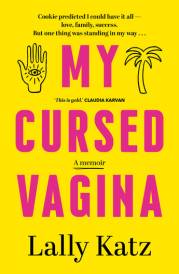

John Cho Searching

He Just Missed His Daughter's Final Call

Cast: John Cho, Debra Messing, Joseph Lee, Michelle La, Sara Sohn

Director: Aneesh Chaganty

Genre: Drama, Thriller

Running Time: 102 minutes

Synopsis: After David Kim (John Cho)'s 16-year-old daughter goes missing, a local investigation is opened and a detective is assigned to the case. But 37 hours later and without a single lead, David decides to search the one place no one has looked yet, where all secrets are kept today: his daughter's laptop. In a hyper-modern thriller told via the technology devices we use every day to communicate, David must trace his daughter's digital footprints before she disappears forever.

Searching

Release Date: September 13th, 2018

About The Production

Searching began when two young filmmakers (writer/director Aneesh Chaganty and writer/producer Sev Ohanian along with veteran producer Timur Bekmambetov) sought to tell a hyper-modern thriller told via the technology and devices we use every day to communicate. At the center of the mystery is beloved, missing daughter Margot, determined father David and sympathetic but no-nonsense Detective Vick. They are brought together by Margot's sudden and baffling disappearance. The hunt is abetted by our modern tools of communication – social media, texts, emails, a life played out in photos and video snippets, saved on computer files for safekeeping. But all is not what it seems. We are what we hide in our mobile devices, which often conceal as much as they reveal. Our virtual identities are subjective constructs at best and David learns more about his daughter than he had ever known with every digital clue. In telling the story, the filmmakers use a screen-based language of storytelling that authentically depicts the way we interact today and explores the reality of a modern parent/child connection in the Internet age.

Our modern modes of communication provide instant ways to present and reinvent ourselves. The virtual world is especially enticing to teenagers pushing boundaries and exploring their identities, while also offering life affirming promise with a lurking menace. Searching investigates the age-old parental dilemma in a brand new cinematic way – how much latitude to give a child, how much independence to afford them, and when to reign them in – made especially harder by social media. The question lies in who are they connecting to and who are they becoming? It is a big-screen thriller told in real time, in a new way that is also super familiar – these are the devices we all use and thus far audiences are embracing to this crowd pleaser. It won the Audience Award at Sundance.

Chaganty and Ohanian make their feature debuts with Searching but met prior at USC in a film production class, where Ohanian was a graduate teaching assistant and Chaganty one of his strong students. "Aneesh always had the best ideas, a good work ethic, positive energy, an inquisitive mind and you just had a sense that he could be something great."

Student and teacher eventually became writing partners and film collaborators and Ohanian soon established himself as a successful independent producer (Sundance Festival selects "Fruitvale Station," "Results," and "The Intervention" among his credits). At this point, Chaganty worked for Google in New York creating short-form content, including "Google Glass: Seeds," a short film shot entirely with Google Glass. It was at the behest of a small program called The Creative Collective, designed to ascertain how the product could be implemented as a filmmaking tool. Creating this screen-based content - screen in the most current interactive sense of the word – required both technical and operational workflow skills Chaganty and Ohanian would apply to the production of Searching. In many ways, Chaganty was perfectly poised for Searching – his Google projects and commercial work gave him the experience and pedigree to lead to feature filmmaking, particularly this innovative approach to cinema.

Meanwhile, filmmaker Timur Bekmambetov was also experimenting with a new cinematic approach that better illustrated our modern communication paradigms. He calls this concept screen-life and describes it as a new film language. The notion occurred to him in 2012 during a Skype conversation with his producing partner. After the business discussion ended, this colleague forgot to turn off the screen sharing function. Bekmambetov saw him search the Internet, send messages on Facebook, place orders on Amazon, etc. At that moment, he glimpsed into his friend's inner life, his motivations, his concerns in real time, merely based on what windows were open, the way he moved his cursor, the choices he made and the manner in which he typed. A text message, from the typing to the back spacing to the decision to send or delete revealed a kaleidoscope of emotions and all in a singularly visual way.

"It's very simple. We spend half of our time now in front of us on our devices and it means our 'screen life' is quite important to us and reveals so much about us. Our entire lives play out on our devices – fear, love, friendship, betrayal, our fondest memories, our silliest moments. It seemed to me that there wasn't a way to tell stories about today's world and today's characters without showing our screens. Because multiple dramatic life events play out on our phones and computers. Most importantly we make impactful moral choices today with these instruments. To be able to depict this I think is a way to authentically reflect who we are today, collectively," Bekmambetov explains.

Inspired by this new form of storytelling, Bekmambetov, through his company Bazelevs, began to seek out likeminded young filmmakers who would embrace the screen-life approach. He had some success in 2014 with the hit 2015 thriller "Unfriended," told through a group Skype conversation amongst teenagers that takes a deadly turn, and was looking for young cinephiles to join him in taking the approach to a new level.

"We found those filmmakers in Sev and Aneesh, and they gave us an unbelievably great teaser pitch. It was clear that they totally understood the beauty and possibility of this new language and also had a fantastic sensibility for story and character" Bekmambetov relays. Ohanian and Chaganty, thinking almost entirely in terms of short form content, had come up with an idea about a father who breaks into his missing daughter's laptop, figuring it would be part of a digital anthology series. "We put together a pitch for a six-minute film," recalls Chaganty, and at the end of the pitch, Bazelevs said "We like it – but we love it as a feature." "I wasn't interested in a short film, but I could definitely see the possibility of it as a fulllength feature. And they had great ideas. I personally love to encourage young filmmakers, they usually have the boldest, most creative ideas and Aneesh and Sev were exceptional examples of that," Bekmambetov says.

Bazelevs suggested that the pair write the feature and Chaganty would direct. And Chaganty initially declined.

"I could have kicked him under the table!" recalls Ohanian. Leaving the meeting with the promise that they would "think about it," Ohanian and Chaganty took some time to figure out if the feature length concept would work.

"I worried that turning our short idea into a feature script would feel like we were stretching an idea thin instead of expanding on it organically." Chaganty says about his initial hesitation. "But we kept talking about it."

Ultimately, they signed on to write and direct, mostly based on being inspired by montage opening sequences from other films that cracked their creative conundrum. In a curious moment of serendipity, both men hatched the same concept for the film's first few minutes while thousands of miles apart.

Their mutual idea revolved around telling the backstory of the Kim family through a screen-life montage, illustrating the delicate and compelling emotional universe of the main characters' lives through our everyday communication devices. The prologue of Searching guides us through the video chats, calendar entries, home movies shot on phones, and text messages that tell the story of the birth of Margot Kim, the happy early years, and the darker days to follow.

Their mutual idea revolved around telling the backstory of the Kim family through a screen-life montage, illustrating the delicate and compelling emotional universe of the main characters' lives through our everyday communication devices. The prologue of Searching guides us through the video chats, calendar entries, home movies shot on phones, and text messages that tell the story of the birth of Margot Kim, the happy early years, and the darker days to follow.

"One night we texted each other at the same time, saying, "Hey, I just came up with the opening scene." And we called each other, and we both pitched each other the same thing, which is what ended up in the movie, which was reminiscent of the opening scene in the movie 'Up.' We thought that approach, translated through screen-life, could create characters people cared about, could become invested in them and in the first five minutes, our hope was that it would be both familiar, in that it is how we communicate with each other, and that people would forget that it was an unconventional way to see a movie," Chaganty says.

Indeed, that segment that helped convince actor John Cho that the screen-life storytelling experiment might work: The bulk of the work is done in that opening montage – if that speaks to you, if that gets you, then you're in, and you accept the premise of the movie because you know who that family is," says Cho. "He had to get that right, and he nailed it – when I watched it, I felt like I could give myself to this story and not think too much about the new technique."

In addition to receiving the funding and production support from Bazelevs, they also received creative freedom and some of the ingenious rigs the company had invented specifically for the screen-life format.

"The biggest challenge for any producer is just to find the right filmmaker," says Timur Bekmambetov. "Then you just shake hands. I know that because I am a director myself, and it's very important that when a producer makes a decision about a filmmaker, you have to let them make their own movie and especially with one like this, it was more important for me to be there for them in the edit. We at Bazelevs are looking for talented filmmakers that we can help AND learn from."

Indeed, as much as Searching is shaped the way it reimagines modern technology and digital storytelling, it is, importantly, anchored by a riveting, dramatic mystery with unpredictable twists and a compelling emotional base. "We wanted to make a movie that we wanted to watch," explains Chaganty. "Our favorite kinds of movies are gripping and emotional with a lot of suspense and intrigue, and from day one, we wanted this to be a story where you would just fall into the mystery and almost forget the way it's being told." In developing the screenplay, Chaganty and Ohanian watched dozens of missing person thrillers to see what worked and what didn't, and various strategies filmmakers had employed in order to conceal information and subtly misdirect. "If you look at the actual storyline of Searching," says Chaganty, "you'll see a lot of the traditional elements of the mystery thriller. Our goal was to mirror those things that we loved best and adapt that into the screen-life concept."

To prepare for the shoot, Chaganty borrowed a system he'd used at Google called prototyping, similar to the motion picture industry's "pre-viz" process. Ohanian explains: "In prototyping, they create a version of the project ahead of time with a lot of temp footage and material that they gather on their own. So Aneesh had been used to this workflow, and applied that to this project, and actually, very early on, made an entire version of this film which was very helpful because we were able to really watch the film before we went out and shot any of it, and we were able to solve a lot of problems beforehand. Essentially, we started editing the film seven weeks before we started principal photography," says Ohanian recalls. This mini-movie provided Chaganty with invaluable information that in turn was vital to the actors translating this new film language, including Debra Messing who plays the accomplished and determined police detective Rosemary Vick tackling the case of Kim's missing daughter.

"I was incredibly intrigued. It literally was unlike any film script I had ever read before. The whole thing that makes this movie so original and exciting and forward-thinking is this really thrilling to approach to storytelling in a completely new way," she explains. "Even reading the script was a different experience, and that's what excited me – it was obvious that Aneesh was so clear in his storytelling and the kind of film he wanted to make. At first it was a big leap of faith, but on set there was always a sense of 'this is how we are going to make this work,' with room for tinkering if we needed to. There was always a sense of discovery." In a bit of life imitating art, the digital video communication that becomes another visual platform in the movie became the conduit of her research.

"I thought research was really important because I didn't have any idea about what a missing persons detective job is, really. And so, I was able to speak with two detectives from Los Angeles, via Facetime with them simultaneously. It was wonderful, they were very patient with me, going over everything from what is the protocol as soon as you get the call to going in front of public, speaking about the case and what's expected of that; the dynamics between a victim's family and the detective," Messing recalls.

While her preparation for the part followed a traditional path, filming it was anything but conventional. It also allowed for truer to life experience than typical movie blocking and shooting could have even approximated.

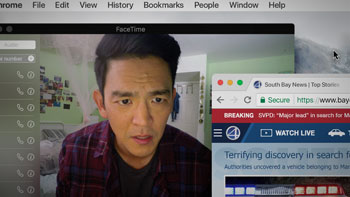

"My first day on set was, I think, the most shocking, because I had a scene with John and I never was in the same room as him. It was incredible. I was in one room with the laptop and the GoPro right on laptop. And he was on the other side of the house with his own laptop and his own GoPro. And we were able to actually do this scene in real time with a video link simultaneously, as we would in real life. There was something so organic, so real about it. In normal filmmaking, you shoot one side and angle or angles and then you move the cameras and lights around and do the same thing from the other side. Everything that was happening with both of us was being recorded and that was really interesting," Messing says.

Occasionally, the process was akin to acting nearly solo against green screen – except the screen was an actual computer and the camera only a small GoPro.

"There were times when Aneesh would say, 'I think it'll be better, instead of looking at John through the Facetime, you should look directly into the camera.' This, is of course completely antithetical to what you learn as an actor but this is also what we do every day when we talk to each other through our devices or social media. So, in that sense it is much more realistic. So, I had to act into a camera, although John's face was on the screen below, in the periphery of my sight line. It was a new acting test for sure," Messing says.

"There were times when Aneesh would say, 'I think it'll be better, instead of looking at John through the Facetime, you should look directly into the camera.' This, is of course completely antithetical to what you learn as an actor but this is also what we do every day when we talk to each other through our devices or social media. So, in that sense it is much more realistic. So, I had to act into a camera, although John's face was on the screen below, in the periphery of my sight line. It was a new acting test for sure," Messing says.

John Cho, drawn to the emotional arc of the characters, David Kim's in particular, as well as the twists and turn of the plot, was also fascinated and challenged by the screen-life approach in telling the story. Though initially skeptical, he ultimately warmed to the acting challenge presented by the new format.

"I was surprised that one could tell this story, so large in scope and drama, through this paradigm. I wasn't sure how we would be able to convey all this emotion in this way and stay honest but I was pleasantly surprised. It's challenging for sure, the lens is very close to you so there is no way you can be fake. So, in that way, it is very truthful. It's typically one angle per scene and it's all told from David's POV so it's tough in the sense that there are no escapes, you have to be incredibly focused and present because you can't count on coverage to cover up your mistakes. It was a very exacting and emotionally intense experience," Cho says.

Michelle La who plays Margot, David Kim's missing daughter, related to her character.

"Margot is a bright, 16-year old person with a lot of life inside her. She grew up in a loving family but throughout the movie we discover she's had a difficult time expressing herself and finding her way through a tragic time in her life. I definitely understood some of what she went through. Being 16 is not easy. People sometimes write teenagers off as 'misunderstood' when it can be much deeper than that and trying to navigate all those emotions can be overwhelming," she says.

La also related to the unconventional filming technique.

"Because I am a millennial myself, I have been exposed to different technology, I grew up with this form of communication and actually it felt a lot easier and more natural for me to be present and in the moment with gadgets and gizmos in front of me or in my hand," she says. Because this screen-life approach was new to everyone, the actors and their young director embarked on a creative journey together, discovering and defining their process as they went along. The bulk of the storytelling fell to Cho and Messing, whose ongoing professional relationship, revealed entirely through their screen connections, reflect the direction of the story and the fate of the missing Margot. "We were very lucky that John and Debra joined this project," says Chaganty. "The more we made the movie, the more we learned about how to make this movie and the more we realized how much that process impacted the actors. Both John and Debra were always game for that constantly changing challenge."

"It was an instance in which more than any other performance, I had to rely completely on the director," adds Cho. "Working basically in extreme close-up all the time was very strange and often when we filmed, we didn't have all of that visual detail that you see in the final movie – so Aneesh would have to talk me through what David was looking at. Tiny eyeline movements became so important, as I had to sync up my look to what would be on the screen."

For Messing's Detective Vick, seemingly determined and objective in her goal to solve the mystery of Margot's disappearance, creating the various layers of her motivations were critical to her performance and she found a willing partner in Chaganty, "I'm a single, working mother of a boy, so I immediately identified with the basic facts of her life," she explains. "Aneesh was so great about working with me on a timeline and answering all of my questions – it was like having a rehearsal and discovery time before we got onto the set."

All the actors enjoyed a very interactive relationship with cinematographer Juan Sebastian Baron. During the shoot, Baron juggled the technical and creative aspects of more than a dozen recording devices used to film Searching, each which revealed its own rules and constraints. And he found himself less occupied with lens choice or dolly movement, since most of the "cameras" recording the action were fixed, whether attached to a computer or mimicking surveillance optics.

Baron, who met Chaganty in film school, relished the opportunity to break new cinematic ground with Searching but was also grateful some of that had been done before him.

"Luckily, Bazelevs, our production company, had developed a lot of technology in-house that helped us accomplish this, like some of those FaceTime conversations and stuff. They had engineered this rig with dummy laptops with GoPros attached to them and LED lights to kind of mimic the screen, and they all go into this security camera switcher system – it's this very Frankenstein contraption, but it really was the best way to solve the problem of doing scenes where the actors are talking to each other via FaceTime. And it also gave Aneesh the opportunity to watch playback and kind of have a more traditional director relationship with his actors," he says. way.

Baron and Chaganty took this screen-life approach to the next level in a very personal "It was really fun. We shot with iPhones – our A camera iPhone was Aneesh's personal phone! We took the screen-life technique up a notch and Bazelevs was as excited about it as we were. It was well beyond a FaceTime chat or Google Hangout. We involved all sorts of different media. We even had traditional news footage but it would be revealed and seen the way most of us get our news, through an online portal and viewed through a computer. So that was a big logistical challenge. We really had to break down every piece of content that was going to be presented in the film, and had to break it down into time period, what kind of camera would we ideally want to capture this on, and then realistically – because we couldn't have 30 cameras – we had to break it down into the types of cameras that could give us different looks and different styles that would be authentic."

Authenticity was the overarching goal and as Baron points out, technical approach and performance intersected as everyone tried to discern a way to achieve that. Ultimately, John Cho became a de facto member of the live action camera crew.

"The prep process for this movie was a lot of not only technical conversations, but we also had a lot of philosophical conversations, of 'how are we going to do this? What is our approach? What does this mean? Are we going to have the actors operate the camera, is that part of our philosophy for this? Are we going to do a lot of the deterioration of the footage in post, or are we going to capture it as real as possible? Aneesh's mandate from Day One really was, 'I want to make this as real as possible. I want people to feel connected to this movie because it's really relatable and very honest.' In keeping with that, the cinematography has to be grounded. It has to be just as organic. And a lot of that rested on John Cho. We knew that if we wanted this movie to feel like John Cho's point of view, there was no substitute to him holding the phone, among other things. And that's intimidating, to be acting and also serving as a kind of camera operator. And seeing yourself as you are acting. After a few takes, everybody really embraced it, and everybody went along with how different it was. And I think it takes a lot of courage for an actor to jump into that," Baron says.

Production designer Angel Herrera had several tasks unique to Searching – he created traditional movie sets that would be seen through a filter of a computer screen or mobile device; it is a narrative film with a cinema verite feel coupled with graphic design.

"It was very realistic production design, but it was also supposed to feel like a documentary. Much of the setting is a backdrop especially when the characters talk directly to camera. It was a challenge to design in a way that you could get an idea across of who these people were and what their world was. But on the other hand, how to keep it as simple as possible so it wouldn't feel like a manufactured world for a movie. That was the fine line that we walked the entire time – how much can we push design and how much do we let things fall to the background, literally and figuratively? The trick was to establish a composition of an object that would be strong enough in the frame of a tiny setting. Do we find him with two bookshelves or a window to bookshelf and what does that mean? What's that color pop or shape that's behind us? Many times, it was more about graphic design and the shapes we put in the background as opposed to what exactly is literally the object back there," Herrera says.

The color scheme became a useful tool in underscoring the characters and establishing a sense of place.

"We tried to assign a specific palette to each character so we could identify who we were talking to immediately not only just from the actor but from the space, the feeling. Margot's tones were greens, yellows, soft cream colors. She also had a star motif, especially with her and her mother, sort of a celestial reference, her mother in the heavens and a metaphor of escape for Margot. Whenever she was with her mother, we pushed the yellow color, like a ray of sunshine. With her father David, we stuck more with browns and reds. His brother had a connection to his niece, so he had a color palette similar to Margot, warmer greens and yellows. We stayed in the blue hues for the detective, because it felt like cop color but also she was the only character assigned a cool tone," Herrera says.

Herrera builds most of his sets in three-story house in Laguna Canyon, California, which became a veritable sound stage but one of his biggest sets was outdoors.

"We had spent so many days in the house that going outside and filming the car being fished out of the lake felt enormous even though it was the exact same team behind the camera. There were a lot more people in the frame and picture cars; We had to lay down fake grass and there was a lot of staging involved," Herrera recalls.

There was a point where Herrera handed off some of the visuals to the editing team, which he says made his job on set more focused.

"We knew a lot of the graphics and actual typing of text messages etc. had to be added in post. That mini-movie Aneesh made ahead of shooting was very helpful in terms of figuring out the pacing and what was going to be visually important from my end, what my team had to concentrate on during production and what we could leave to the editors," Herrera notes.

While the film shot for a limited number of days, the edit was substantially longer and required two editors. Will Merrick and Nick Johnson. In a sense, their work began even before principal photography, working with Chaganty to stitch together his pre-visualized DIY movie. The overall process of assembling the film paralleled that of an animated motion picture in that layer by layer, each new pass added more critical information to the original "mini-movie" that Chaganty had constructed. Apart from the actors' performances and physical sets, assets that were filmed, staged, or imaged as a screen capture, website, blog comment, text message, or digital news clip all had to be added in the edit. As filming continued, the elements from that initial rough cut were slowly replaced by the more designed, refined, and detailed versions. "We began working on editing seven weeks before production started, with a totally blank timeline and worked with Aneesh, taking pictures of the space and screenshotting web pages to build out kind of an animatic, like a Pixar-style storyboard of what the movie was going to look like, which was used during production," Merrick explains.

"So, we were refining the story with the director and producer in the room, so that essentially, when they started shooting, they knew exactly what they were shooting, they knew what the eye-lines should be, what they would see in terms of the actual set, etc. and that helped tremendously because ultimately, we didn't have to do as many pick-ups as we might have otherwise had to do, had we not had the pre-viz," Johnson adds.

This unusual approach to the edit also led them away from the Avid system typically used to cut films.

"The actual editing was all done in Premiere Pro, and the reason we chose Premiere and Adobe was because they have a really nice ecosystem, where you can send assets over to After Effects very smoothly, and then we can ultimately finish everything in After Effects, which for us was essential. We've both cut stuff in Avid, as well as Premiere but for this particular project, with all the effects that we knew we were going to have to do, that Premiere and the Adobe system made the most sense," Johnson says.

"We love Avid but it would have been too weird of a workflow. We'd have been too locked in," Merrick adds.

In the case of Searching, "effects" took on a new meaning.

"Essentially, everything that didn't just come straight out of a camera on set was an effect that we had to create. So, say the top bar of Google Chrome had to all be created from scratch,'" says Merrick.

"We worked with an outside vendor named Neon Robotic to create some templates for us and they were a huge help for building some of the more complex assets like iMessage and Chrome and Chrome docs, stuff like that. But then other than that, it was just me and Will in (Adobe) After Effects and another design tool, Illustrator, replicating everything you see on a computer screen, and then meticulously key-framing and moving the mouse around and animating every asset that you see," Johnson notes.

The editors did try to treat Searching as a "traditional movie" in that they were concerned about "…pacing and transitions and making sure we cut the conversations carefully so the dialogue worked," Johnson relates. Specific to Searching, he adds, is the first-person perspective of John Cho's character.

"The whole thing is from his perspective, so you're constantly trying to exploit those little moments where he might not be on screen, but you can still reveal his POV and mindset. So, for instance, a mouse might hesitate before clicking on a button, or it might move a little bit slower, or it might move a little bit faster if he's really excited. So little things like that were really fun because it felt like acting. The actual edit of scenes felt like performance."

The Bazelevs team and producer Natalie Qasabian proved to be vital creative partners in the execution of these complex series of assignments and production challenges for a "live action" film assembled like an animated one.

"The entire process of editing was over a year. We had two editors working full time, and even though we were working in the modern age of digital, non-linear editing, the level of detail we had to bring to each scene felt like we were cutting on an old Moviola," says Ohanian. "The rendering was so complex – we'd ask the editors to make a change, and they'd say, 'come back in a couple of hours' when we are so used to seeing things instantly, because of the sheer size of the files and programs we were working with."

While the process was painstaking and pioneering, the result is a movie that resonates with the familiar iconography and discourse of contemporary life.

While the process was painstaking and pioneering, the result is a movie that resonates with the familiar iconography and discourse of contemporary life.

"Audiences will recognise themselves in every click and movement of the mouse, every notification, every sound, everything that we now use to experience everyday life in a way that is also compelling and cinematic," says Bekmambetov. "This approach, we hope, helps the audience relate to the character in an intimate way – you see how the character is writing something, deleting it, then writing something else, debating whether to save or delete a cherished memory – traditional filmmaking relies on techniques like voiceover to do that and to me that seems less real and certainly less visual. Based on our previous screen-life movies, it does seem that audiences are ready to embrace this new form of cinema. But of course, it only works if you have a filmmaker who can create meaningful characters and tell great stories and discover something emotionally."

"Ever since I picked up a camera I've always liked films that told stories we know in a way that we don't expect. Searching takes that to a whole new level. But when we were filming, I wasn't thinking about the novelty of the approach. When you're in it, you're not thinking you might be doing something groundbreaking, you're just doing the best work you can, trying to be true to the characters and story. But every once in a while, during this process, I would take a step back and think 'what we are making could be really, really cool,'" sums up Chaganty.

Searching

Release Date: September 13th, 2018

MORE